My younger son informed me one day that he had been a tiger in India. Curious, I asked him, “How do you know?” “Sometimes on the soccer field,” he said, “I have a sudden access of grace and agility, like a tiger.” (He was about ten at the time but read beyond his years, and his memory was better than I’d supposed.) Athletes encounter such moments but seldom credit them to so close a relationship to our own animal nature. Most of us who do not live near wild animals like tigers—or lions, cheetahs, rhinoceroses—experience them primarily through photographs, and perhaps now and then on a trip to a zoo with a child in tow. Photography stokes and channels our fascination and wonder, our curiosity and response to whatever strikes us as exotic, our respect for fearsome power and our awe in the face of such strange beauties. And it reinforces a tendency, somewhat less vivid than my son’s, to compare and conflate ourselves to the animal kingdom, as in: Lion-hearted. Wolfish. Foxy.

Genesis promised us dominion over all of creation, but Africa’s large animals make that promise seem flimsy and rivet attention to nature’s mysterious and unbridled creativity. Early photographers recognized the monumental importance of such creatures but could do little about it other than photographing those that sat still in a zoo. Once film was fast enough, telephoto lenses precise enough and color film good enough, photographs of dangerous and elusive animals in their native habitats became a reliable and popular source of vicarious thrills.

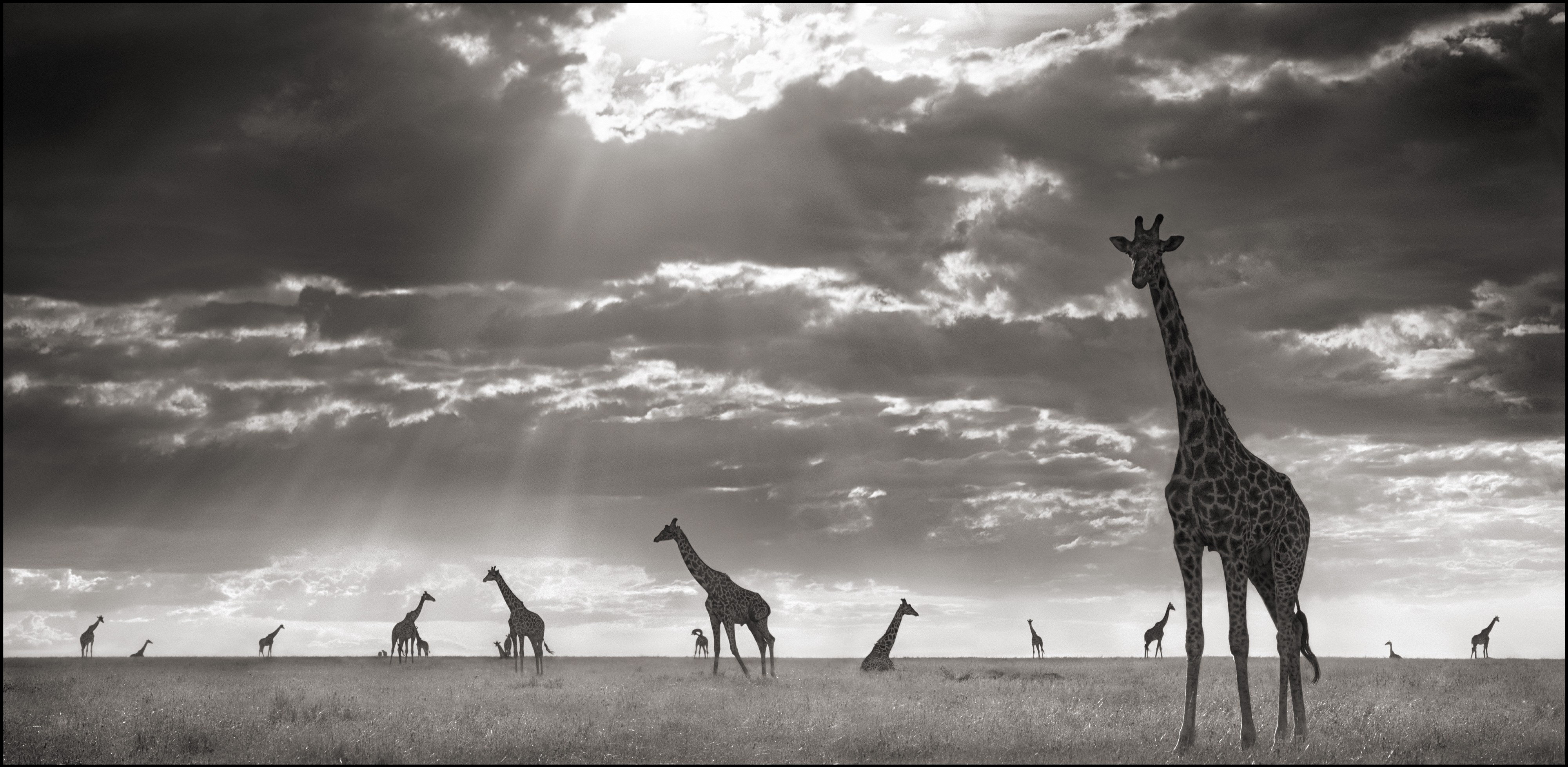

Nick Brandt’s pictures present a more complex set of goals and achievements than the usual run of reports from the African wild. He is on firm footing in the areas of beauty, awe, and sympathy, and he navigates a sure course across the diverse regions of portraiture, emblem, environment, nostalgia, narrative, and entropy. To begin with, his images are quite beautiful, no mean feat but common enough in the genre. For some years, the art-photography world disdained beauty as an inferior approach, but wild animal photography, which generally appealed to a different audience and showed in different venues, was excused. Brandt’s large, soft-sepia-toned prints are designed for aesthetic consideration yet often bypass conventional and conventionally beautiful compositions. “Giraffes in Evening Light”, for instance, with one bold giraffe up front, has a row of stick-figure giraffes in the distance describing a rhythm so quirky and disconnected it looks like a John Cage score. Several pictures of giraffes are nearly as eccentric as the species itself: a lone giraffe off to one side in a halo of light as a dark sky moves in, a triptych of giraffes performing neck ballets. Giraffes appear to have an enviable tendency to blunder into sophisticated choreography.

A New View of Animals

forewOrd to a shadow falls by vicki goldberg

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN THE A SHADOW FALLS MONOGRAPH, 2009

forewOrd to a shadow falls by vicki goldberg

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN THE A SHADOW FALLS MONOGRAPH, 2009

Giraffes in Evening Light, Maasai Mara, 2006

Giraffes in Evening Light, Maasai Mara, 2006

His landscape photographs, some of them panoramic, harbor animals that give them meaning. In certain photographs, a single animal holds its own against overwhelming skies and plains. This presentation of a vast terrain, a temporary stand-in for the universe, where a lone figure or tiny group would be a trivial detail were it not the nominal subject, has isolated precedents in nineteenth-century photography by the likes of Adolph Braun and Samuel Bourne in the Alps and Himalayas and occasional others in Egypt and the American West, but the sweep of great and entirely unpopulated landscapes was more popular then and still is—think Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter—and today a sole animal punctuating an enormous space is more likely to be encountered in movie westerns than in still photography.

Yet Brandt’s landscape photographs do more than document an exceptional environment. In these images, a lion or cheetah is not only subject but content, the reason for the picture as well as a figure that concentrates the land’s significance for us. The eye is ineluctably drawn to the animal, and its weight in the picture makes it the equivalent of the land’s expansive grandeur: a distillation, a shortcut, a recognizable and more comprehensible clue to the inchoate feelings such environments evoke.

In other landscapes, Brandt discovers animals and land mirroring and commenting on one another. Zebras swimming in single file across a river while the herd waits to follow suit—a dangerous crossing, for crocodiles wait and currents are strong—form a curve almost identical to the curve of the shore. Elsewhere a solidly focused herd of wildebeests swims away from land that softens and blurs in its wake. In “Elephant Ghost World”, distance, dust, and clouds that have descended from an enormous, darkling sky envelop and set about dissolving these mighty creatures.

Yet Brandt’s landscape photographs do more than document an exceptional environment. In these images, a lion or cheetah is not only subject but content, the reason for the picture as well as a figure that concentrates the land’s significance for us. The eye is ineluctably drawn to the animal, and its weight in the picture makes it the equivalent of the land’s expansive grandeur: a distillation, a shortcut, a recognizable and more comprehensible clue to the inchoate feelings such environments evoke.

In other landscapes, Brandt discovers animals and land mirroring and commenting on one another. Zebras swimming in single file across a river while the herd waits to follow suit—a dangerous crossing, for crocodiles wait and currents are strong—form a curve almost identical to the curve of the shore. Elsewhere a solidly focused herd of wildebeests swims away from land that softens and blurs in its wake. In “Elephant Ghost World”, distance, dust, and clouds that have descended from an enormous, darkling sky envelop and set about dissolving these mighty creatures.

Zebra Crossing River, MASAI MARA,2006

Zebra Crossing River, MASAI MARA,2006

Many pictures convey a rare sense of intimacy, as if Brandt knew the animals, had invited them to sit for his camera, and had a prime portraitist’s intuition of character. This is not to be confused with the illusion of the photographer’s closeness to skittish subjects, which is rife in African animal photography by virtue of telephoto lenses. Brandt doesn’t use one. He works with a medium format camera, and he waits with a zen-like patience for days, even weeks, to become an acceptable presence, to see the maddeningly persistent, clear blue skies do a favor to his photographs by subsiding into clouds, to spot some action or expression worth recording.

The results are portraits of wild animals as surely as Peter Hujar’s pictures of dogs and cows are portraits of domesticated ones. What’s unlikely, and exceptional, is that Brandt has not only, somehow, divined what read as incontrovertible elements of personality and emotion but also captured his subjects, which aren’t about to follow directions, when they slip into attitudes and positions as elegant as any arranged by Arnold Newman for his human high achievers.

It doesn’t require science to determine that animals have at least certain emotions. Besides, long before it was discovered that we have so many genes in common not only with chimps but with mice, humans everywhere tended to anthropomorphize animals, to judge their look and demeanor by what we believe we know about our own kind. Thus it is probably mere projection that finds Brandt’s elephants somber and melancholy, as if they were oppressed by their own wrinkles. A lion that leans his forehead down to his mate’s (“Lions Head to Head”) might only be insisting on his dominance, but it sure looks like affection or at least some kindly, husbandly communication. And Brandt’s photograph of two baboons (“Baboons in Profile”), one a mother with a baby burrowing into her breast and light cutting between the pair like a revelation, becomes an allegory of attachment, family, tenderness, and caring, with a hint of the attendant difficulties in the crown of thorns at the top.

Brandt’s staunch endurance and quick eye combine to produce emblems as well as personal portraits; at times they are one and the same. Animals in perfect profile, some as precisely reflected upside down in shallow water as figures on playing cards, would be ideal illustrations

The results are portraits of wild animals as surely as Peter Hujar’s pictures of dogs and cows are portraits of domesticated ones. What’s unlikely, and exceptional, is that Brandt has not only, somehow, divined what read as incontrovertible elements of personality and emotion but also captured his subjects, which aren’t about to follow directions, when they slip into attitudes and positions as elegant as any arranged by Arnold Newman for his human high achievers.

It doesn’t require science to determine that animals have at least certain emotions. Besides, long before it was discovered that we have so many genes in common not only with chimps but with mice, humans everywhere tended to anthropomorphize animals, to judge their look and demeanor by what we believe we know about our own kind. Thus it is probably mere projection that finds Brandt’s elephants somber and melancholy, as if they were oppressed by their own wrinkles. A lion that leans his forehead down to his mate’s (“Lions Head to Head”) might only be insisting on his dominance, but it sure looks like affection or at least some kindly, husbandly communication. And Brandt’s photograph of two baboons (“Baboons in Profile”), one a mother with a baby burrowing into her breast and light cutting between the pair like a revelation, becomes an allegory of attachment, family, tenderness, and caring, with a hint of the attendant difficulties in the crown of thorns at the top.

Brandt’s staunch endurance and quick eye combine to produce emblems as well as personal portraits; at times they are one and the same. Animals in perfect profile, some as precisely reflected upside down in shallow water as figures on playing cards, would be ideal illustrations

Baboons in Profile, Amboseli, 2007

Baboons in Profile, Amboseli, 2007of The Zebra and The Rhinoceros for an animal encyclopedia. The most minute details can have this effect—a lion’s every whisker, pore, and hair; the scant tufts beneath a cheetah’s belly—as can the most classic or definitive poses—a cheetah seated in profile, as self-possessed as an Egyptian statue of a cat but with its head turned 180 degrees to look back. These make of a single animal an emblem that might well stand for an entire species, an unusual combination of particular and generic that extends Lisette Model’s dictum that the more specific you are, the more general it will be.

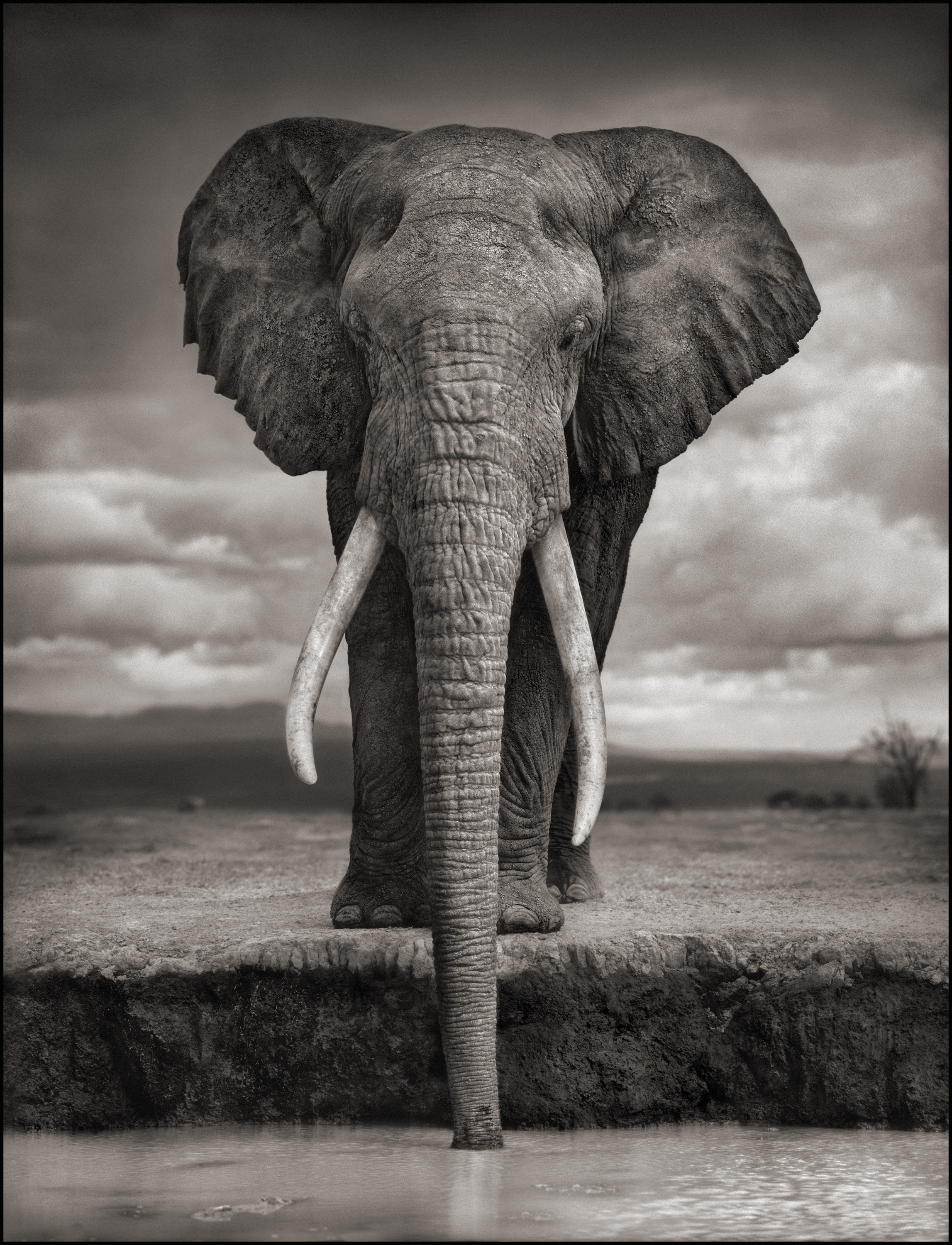

Certain images are emblematic in their configuration alone. Consider the elephant in “Elephant Drinking”. No trained animal could pose more obligingly in a studio than the majestic elephant with his trunk lowered into a lake. Familiar as elephants are from circuses and zoos, I have never seen one exactly like this, perfectly frontal, perfectly symmetrical, perfectly centered within a frame, its trunk plunged straight down into water. This is a statue that breathes, an emblem that drinks.

Certain images are emblematic in their configuration alone. Consider the elephant in “Elephant Drinking”. No trained animal could pose more obligingly in a studio than the majestic elephant with his trunk lowered into a lake. Familiar as elephants are from circuses and zoos, I have never seen one exactly like this, perfectly frontal, perfectly symmetrical, perfectly centered within a frame, its trunk plunged straight down into water. This is a statue that breathes, an emblem that drinks.

Elephant Drinking, Amboseli 2007

Elephant Drinking, Amboseli 2007Brandt is a photographer who lingers in hopes of a vivifying event much longer than photographers do with more approachable subjects. Intelligent though they may be, animals in the wild, even animals visited by safaris, do not vamp for cameras (try to find a human creature you could say that about) and most probably (also unlike humans) do not even know how beautiful they are. It is an old trick of photography, and one of its best, to ferret out beauty and significance where none was intended—I think it was Brassai who said that beauty was not the intention of nature but the result. Still, nature can be extraordinarily generous to its most devoted acolytes with cameras and quicksilver sensibilities, arranging itself in compositions that would do a designer proud.

Surely capturing the image of a lioness jumping from a tree is as improbable as finding three rhinos that have settled themselves in lambent light so their ears and horns graphically echo one another. I suppose the two zebras have turned their heads (“Zebras Turning Heads”) and raised their ears in identical fashion because they hear the same noise, and I am aware they did not don their stripes to match, but what a pas de deux, and how beautifully costumed and performed! And how very obliging of a lion, seeking the only shade in a treeless plain (“Lion Under Leaning Tree”), to lie down under a blasted tree that is poised at a peculiarly abrupt angle and sports intensely tortured curves and a spiky web of twigs. Photographers today are explorers and archaeologists who seek not so much new cultures as newly discovered artifacts for instruction and visual pleasure.

Surely capturing the image of a lioness jumping from a tree is as improbable as finding three rhinos that have settled themselves in lambent light so their ears and horns graphically echo one another. I suppose the two zebras have turned their heads (“Zebras Turning Heads”) and raised their ears in identical fashion because they hear the same noise, and I am aware they did not don their stripes to match, but what a pas de deux, and how beautifully costumed and performed! And how very obliging of a lion, seeking the only shade in a treeless plain (“Lion Under Leaning Tree”), to lie down under a blasted tree that is poised at a peculiarly abrupt angle and sports intensely tortured curves and a spiky web of twigs. Photographers today are explorers and archaeologists who seek not so much new cultures as newly discovered artifacts for instruction and visual pleasure.

Big Life Rangers Holding Tusks of Elephants Killed at the Hands of Man, Amboseli, 2011

Big Life Rangers Holding Tusks of Elephants Killed at the Hands of Man, Amboseli, 2011A Shadow Falls, taken in its entirety, is a love story without a happily ever after. Generally speaking, it’s either love or hate that prompts such obsessive stalking as Brandt engages in, and hate doesn’t express itself so lyrically. The opening of the narrative is lush: an elephant swings across a forest floor where light beaming through a luxurious canopy of leaves falls upon him like a spotlight (“Elephant Cathedral”). What follows includes lakes and rivers, trees in backgrounds, leafy shelters for gorillas. Later, the lake beds dry up, giraffes cross a migration trail on parched land, elephants plod over what looks like a desert without sand. Two giraffes are undismayed by a twister in the distance; it’s a dust devil, one of many that rise off land in the dry season, more often since cattle grazing has caused vicious erosion. The devil, an ominous sign (if not to giraffes), looms like dark magic in a real-life Oz.

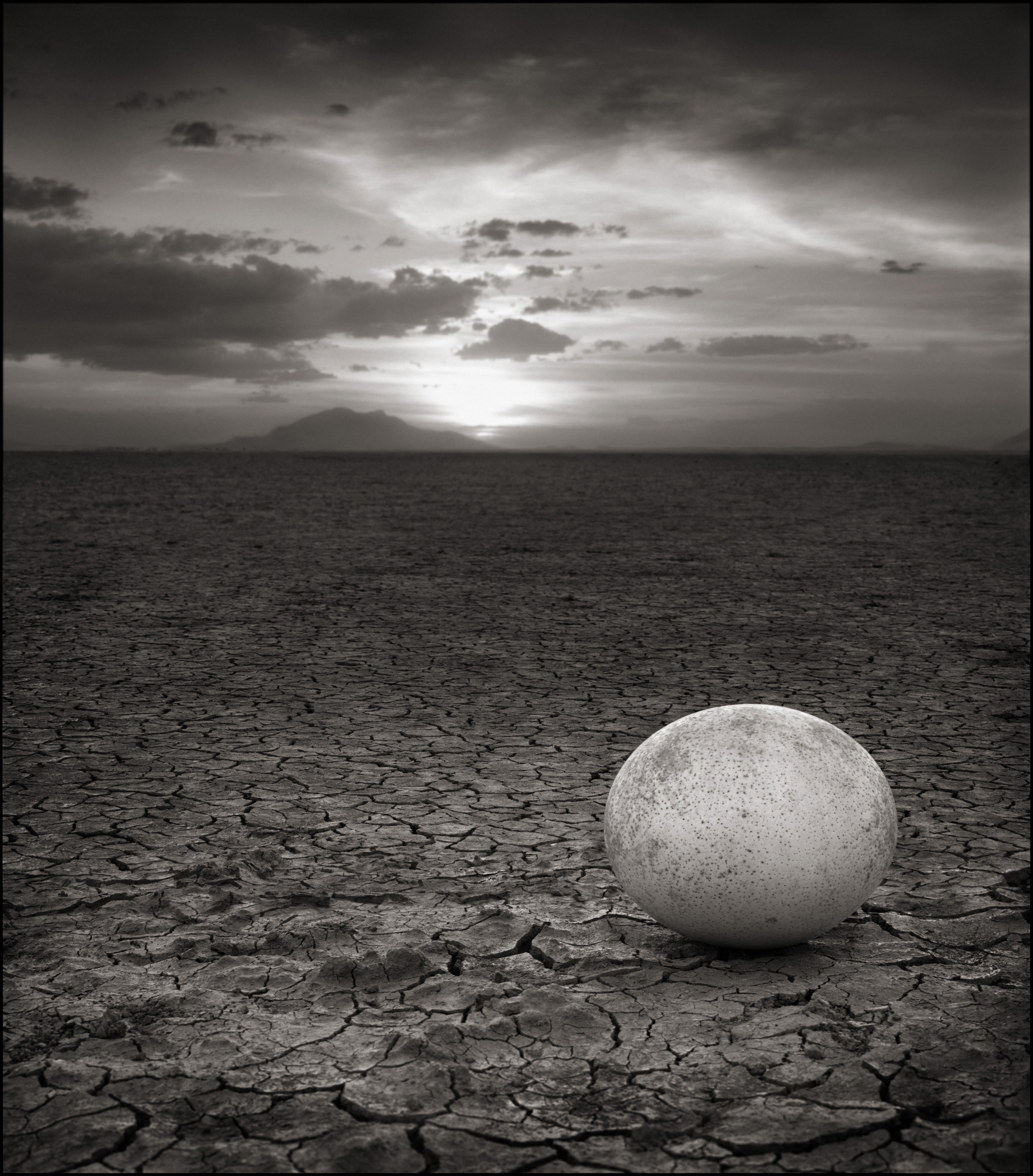

And at the end, at sunset, an abandoned ostrich egg lies on earth that has dried up and cracked open repeatedly, like a brittle piece of china, like a parable of the universe’s experiments with life, which did not succeed where there was no water. Perhaps it represents a planet expiring on hostile soil; Columbus, after all, demonstrated the earth’s roundness to doubters with an egg. However interpreted, the image speaks the language of death, a language easy to read. If humans are destroying the animals, for food, for fear, for greed, we are destroying the land for uncountable reasons, as efficient a way as many another to destroy animals—even when most of the shooting in the African wild these days is done with cameras. At any rate, the land, this earth, is all we have. The animals will go before we do; they haven’t our resources.

Brandt deals subtly with this prospect, not only in sequencing his pictures from abundance to desperation. The sepia tone of his prints instantly suggests nineteenth-century albumen prints, and he has purposely damaged several of them to give a feeling of age, as if we were looking at something that no longer exists: a predictive nostalgia. In this media age, when many are living parts of their lives in some version of virtual reality, the wild animals we reflexively admire or wonder at or stand in awe of could vanish and leave us only their shadowed images, as if they were dead movie stars.

And at the end, at sunset, an abandoned ostrich egg lies on earth that has dried up and cracked open repeatedly, like a brittle piece of china, like a parable of the universe’s experiments with life, which did not succeed where there was no water. Perhaps it represents a planet expiring on hostile soil; Columbus, after all, demonstrated the earth’s roundness to doubters with an egg. However interpreted, the image speaks the language of death, a language easy to read. If humans are destroying the animals, for food, for fear, for greed, we are destroying the land for uncountable reasons, as efficient a way as many another to destroy animals—even when most of the shooting in the African wild these days is done with cameras. At any rate, the land, this earth, is all we have. The animals will go before we do; they haven’t our resources.

Brandt deals subtly with this prospect, not only in sequencing his pictures from abundance to desperation. The sepia tone of his prints instantly suggests nineteenth-century albumen prints, and he has purposely damaged several of them to give a feeling of age, as if we were looking at something that no longer exists: a predictive nostalgia. In this media age, when many are living parts of their lives in some version of virtual reality, the wild animals we reflexively admire or wonder at or stand in awe of could vanish and leave us only their shadowed images, as if they were dead movie stars.

Abandoned Ostrich Egg, Amboseli , 2007

Abandoned Ostrich Egg, Amboseli , 2007Oliver Wendell Holmes had already predicted the replacement of live or solid forms by photographs in 1859: "Every conceivable object of Nature and Art will soon scale off its surface for us. Men will hunt all curious, beautiful, grand objects, as they hunt the cattle in South America, for their skins, and leave the carcasses as of little worth. . . . The time will come when a man who wishes to see any object, natural or artificial, will go to the Imperial, National or City Stereographic Library and call for its skin or form, as he would a book at any common library.” In 1973, the film Soylent Green foresaw a devastated future when global warming and overpopulation has erased almost all growth, food is manufactured as pellets, and animal life has collapsed into images. The authorities offer people who can no longer take the deprivations of this world an opportunity for happy assisted suicide in a room where videos of deer gamboling in leafy forests, something young people cannot even imagine, scroll by like a vision of paradise.

Nick Brandt’s photographs are eloquent testimony to what we could lose. May they never grace his subjects’ tombstones and write their awesome epitaph.

©Vicki Goldberg

Nick Brandt’s photographs are eloquent testimony to what we could lose. May they never grace his subjects’ tombstones and write their awesome epitaph.

©Vicki Goldberg

© 2024, Nick Brandt. All rights reserved.