It's six months since I was last in East Africa. I'm at home, sitting outside on a clear, warm winter's day in the green Santa Monica Mountains of southern California. But even though it’s a beautiful day in a beautiful setting, I'm yearning to be back on a dusty, bone-dry lake bed in East Africa. I'm looking at some photos of an elephant on my contact sheets, an elephant that I photographed those six months ago. And I'm wondering how she's faring. How her herd is faring. This isn't sentimentality on my part. I wish that's all it was.

When I was last there, in Kenya's Amboseli National Park, it was July. Barely into the long dry season that lasts until November. But already, what has become an unpleasant annual drama was unfolding.

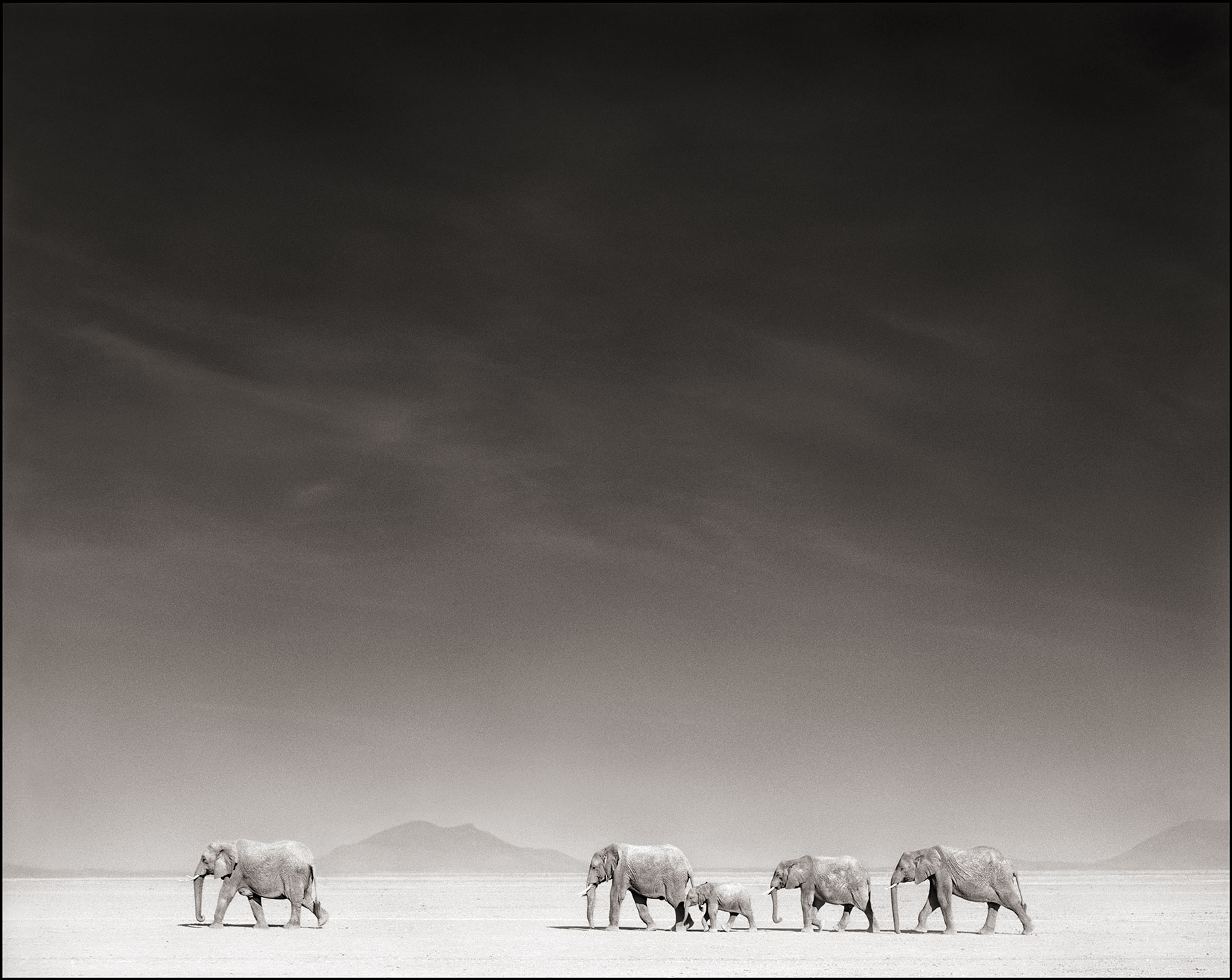

Every morning, my guide and I would drive out onto the vast dry lake bed. There we would wait for a sight that hypnotizes me more than any other here in Africa: one elephant herd after another coming down out of the hills circling Amboseli, where they quietly cross the lake bed in long caravan-like lines toward the marshes at the center of the park. But most mornings, we wouldn't see those elephant herds. We would see something quite different. It would start as distant plumes of dust. But gradually they would grow. And grow. And grow. Until 180 degrees of view across the lake bed was dominated by this dust. Getting closer, until finally, through the heat mirage, the cause of the dust was revealed. An unending line of shimmering black shapes.

Cattle. Tens of thousands of them. The Maasai were bringing their vast herds of cattle into the park, the National Park, to water. And the dry season had not even really begun. Inexplicably, it seemed, no-one from the Kenya Wildlife Service, which manages the park, stopped them.

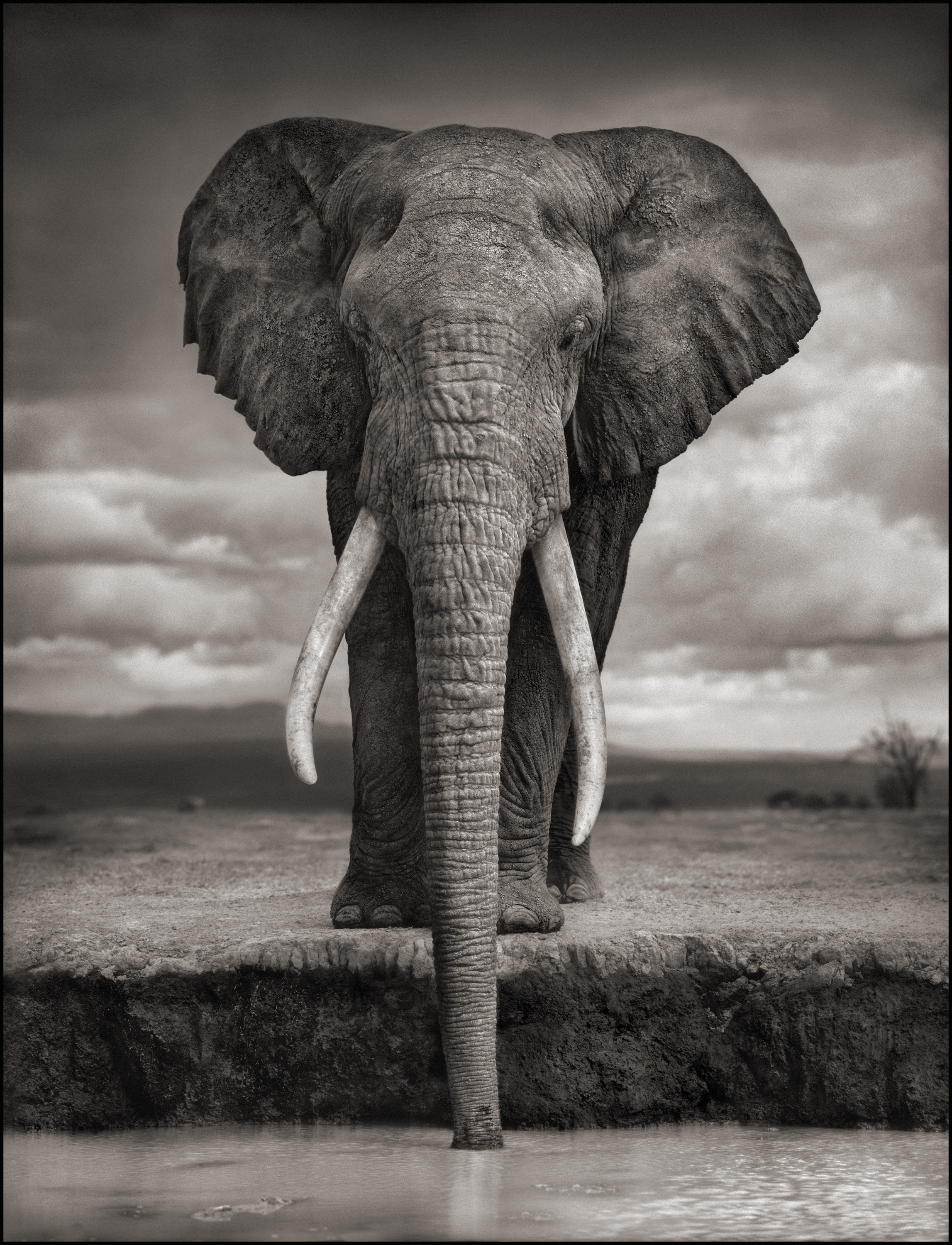

And the elephants? They're frightened of the cattle's owners, the human beings. Because, of course, when the elephants are outside the park, they're unprotected, and being unprotected, sometimes, inevitably, something bad happens to them. They get shot by poachers. They get speared by herdsmen protecting their cattle. As a result, the numbers of giant bulls, with their glorious majestic tusks that can reach down to the ground, have dwindled to just a handful. Elephants leave the park, because it's really pretty small, to go foraging for fresh food. And at some point, something happens, and they never come back.

If you look at my photos of elephant herds crossing the lake bed, what you're not seeing is something that happens with ever-greater frequency : their crossings being aborted by these giant herds of cattle also crossing the lake bed to drink the same water. The elephants become frightened and retreat back into the hills, away from the water and food they need. If it's as tough as this in the most famous park for elephants in Africa, you can imagine what it's like outside the parks.

introduction by nick brandt

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN THE A SHADOW FALLS MONOGRAPH, 2009

Elephant Drinking, Amboseli 2007

Elephant Drinking, Amboseli 2007 Elephants on bleached lake bed, AMBOSELI, 2008

Elephants on bleached lake bed, AMBOSELI, 2008

So why does the Kenya Wildlife Service do nothing to stop the Maasai with their thousands of cattle? Because there’s a vicious circle in motion, a great, complicated irony to the future of conservation in Africa.

There is really only one way for wildlife to survive in twenty-first century Africa: Make it profitable to keep the animals alive for the people who live alongside and near them.

The Maasai around Amboseli justifiably demanded, and got, a greater share in the profits from all the tourists visiting Amboseli. This encourages them to leave the local wildlife alone. The new eco-money helps pay for school buildings and medical clinics, all good things. This improved quality of life attracts yet more Maasai to the area around the park, and herein lies the problem - the new settlers bring with them yet more thousands of cattle in need of food and water. The cattle speed the erosion to the land, and the water table keeps dropping due to global warming and diminished rainfall.

So when the dry season comes, there's just one place the Maasai can take all their cattle for water: Amboseli's marshes. Ground zero for the wildlife of the region. If the Kenya Wildlife Service denies the Maasai access to the park's precious water, then many of the cattle will die. Then all goodwill to the wildlife evaporates, and with that, so goes the wildlife.

This story is getting played out in various ways all across Africa: man and animal fighting for their share of ever-diminishing resources.

In the West, most of us - whether we like to admit it or not - have a comparatively easy life: few of us are likely to starve for lack of food. We are right to condemn the poaching, the murder, of animals for brazen profit, but we should be less judgmental of poaching that can and will increasingly occur out of necessity. When the crops have failed and the land is eroded from droughts and global warming, you too might kill the last zebra wandering through the bush to feed your family.

In 1995 I first drove the main road from Nairobi down through southern Kenya to Arusha in northern Tanzania. Along the way, in completely unprotected areas, I saw giraffes, zebras, gazelles, impalas, wildebeest. A few months ago, just thirteen years later, I made the same drive. I didn't see a single wild animal the entire four-hour drive. It's not that they've moved elsewhere. It's that they've been wiped out, turned into bush meat.

Once you subtract all the unprotected areas of the world, of Africa, the ‘officially protected’ areas left over for these animals is frighteningly meagre and vulnerable. Everything really is imminently finite. When I see a dead baby zebra caught in a poacher's snare in the middle of the most famous national park in Africa, or when I see an elephant with half his trunk missing, ripped off by a similar snare, I know that nowhere is safe.

So everything is connected - we have to help the people that live alongside the animals, not just the animals. The extraordinarily complicated part is how we find solutions to the vicious circle in places like Amboseli.

But sometimes, when I’m there alone on the plains, things are so much more....simple. For me, one of those times was in October 2006, in the Northern Serengeti.

That afternoon, we came upon a group of elephants under a large acacia tree on the plains. One of the elephants, a female, was very agitated. She kept moving back and forth, lying down, then getting up again. Something was making her very uncomfortable.

The other elephants began to come over to her, where they jostled restlessly amongst themselves, back and forth, round and round. And then suddenly, the female's waters broke. The other elephants became still more agitated, all of them bumping excitedly into one another.

Then, barely a minute later, the female gave birth. Looking like it was factory-sealed in cream-colored elephant plastic, a package of new baby elephant slipped out of her into the grass. The baby broke through the foetal sac, its eyes blinking in the blinding sunlight for the first time.

Within seconds, the mother and the matriarch of the group were roughly pushing and prodding the baby with their legs and trunks to get up, get up. Over and over again, the baby started to rise up on its shaky legs only to collapse again. The other elephants continued to circle excitedly, coming over to the mother and baby as if to welcome it into the fold. The matriarch put her trunk into her mouth, drew water out from her stomach, and sprayed it over herself. The absolute unfettered delight and joy of these elephants was astonishing to see.

After fifteen minutes of being constantly pushed and prodded by the mother and matriarch, the baby got up and wobbled around. After only another thirty minutes, learning to co-ordinate his legs, he did a kind of lollopy four-legged dance, following his mother as she led him out into the open and back to the shade. And then they headed off across the plains. The baby trundling along now through the grass with his mother, looking as if he'd been born a month ago, not an hour ago.

We stayed with the elephants until dark, as they walked several miles across the vast, rolling sea of grass. One hour old, the baby was fully in his element, striking out ahead, sniffing the earth, pottering alongside the others, taking in the barrage of sights, sounds, and smells of the East African savannah.

In the same year that this baby was born, 2006, one Asian trafficker alone was found to have smuggled into Hong Kong forty tons of ivory. Those forty tons - just the tip of the iceberg -represent approximately four-thousand killed elephants. Four thousand elephants who should have been experiencing what that baby was experiencing, and what we humans were privileged and enraptured to behold.

I find it hard not to become deeply angered by the destruction and disregard of animal life perpetrated by humans. It may be the destruction that led to pointless trinkets and baubles carved from an elephant's tusk (which looked far more beautiful on the original elephant). It may be the destruction of the countless millions of fish (and dolphins, and turtles, and on and on) caught by fishing trawlers, only to be thrown back into the ocean dead, their lives wasted for no reason at all. Or it may be the ongoing epic abuse of animals subjected to the misery and horror of industrial factory farming. Of course, the list of destruction and abuse could extend to the last page of this book.

For me, every creature on this planet has an equal right to live. Whether human being, Serengeti elephant, or factory farm cow.

This is why I take these photographs. I hope that maybe you will see these animals, these non-humans, in the way that I do - as not so very different from us.

I photograph these animals - that specific elephant or cheetah or lion that has drawn my eye - in the same way I would a human being, watching for the right ‘pose’ that hopefully will best capture his or her spirit. (Although frustratingly, I can't ask the animals to take a small step to the left, or lift their head a little).

This means getting close. It's one reason why I don't use telephoto lenses. I like to frame the animals within the context of their world - the sky and landscape - rather than within a telephoto blur of scrubby ground and bushes. Other times, I'm searching for a panoramic view that I hope will convey some semblance of the rare synchronized spectacle of animals and landscape and light that can unfold, if one is very fortunate and patient.

Portrait or panorama, it can take weeks to get a photograph. 99% of the time, I'm just waiting. Waiting all day next to a pride of sleeping lions to wake up (and chances are that they won't). Waiting for a herd of elephants to stop eating and emerge from the bushes into the open (and again, chances are that they won't). But during these hours, time takes on a kind of peaceful flow.

In the ‘modern world’, we're always rushing, multi-tasking, impatient. Here out on the African plains, I'm always intrigued to find myself strangely happy to just sit near these animals all day and just wait. And wait.....

Meanwhile, back home, I miss the mornings spent in the midst of a herd of elephants when, as they mill quietly around our vehicle, completely relaxed in spite of our proximity, I'm truly contented.

I miss those times when small groups of giraffe congregate into one giant herd out on the plains, their figures like so many chess pieces under yet another startling East African sky. I miss witnessing the groups of male giraffes battling with another; the ballet of giraffes sweeping their heads up toward the sky and then smashing them down into one another, a mesmerizing combination of grace and violence.

I miss those electrifying moments in close proximity to a pride of lions when a storm comes in, and as the wind blows, the lions rise from their sleep and start moving, looking like they might strike the perfect pose for a portrait. Or a giant silverback gorilla, having spent all day sitting chest-deep in wild celery, rises up before me, an astonishing presence standing full figure for his portrait.

I miss the most electrifying, charged moment of all when, after hours of hovering by the riverbank, one wildebeest will take that first step, and then suddenly, thousands of wildebeest and zebra decide, in an explosion of action and noise and high drama, to risk their lives and cross the river before them, braving what for some will result in their death, from crocodiles or the overwhelming current.

Moments like these occur somewhere in East Africa every day. But with each passing day, they occur with less frequency, as these animals, and these landscapes, fade from view.

But in the meantime, just for now.....please find, in the following pages, some of our companions on this planet.

© Nick Brandt

© 2024, Nick Brandt. All rights reserved.