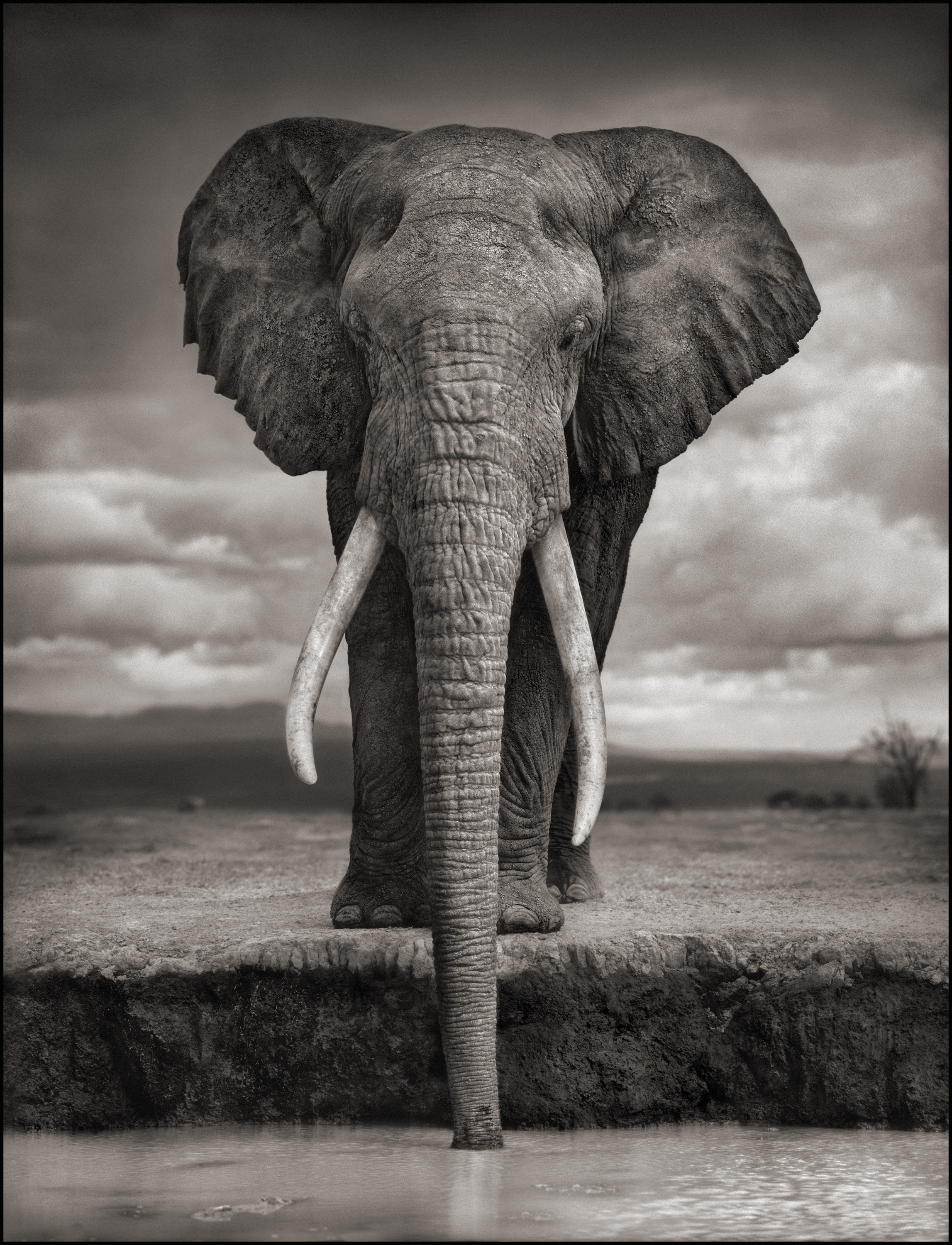

Take a look at the elephant in the photo on the previous page. His name is Igor (as named at birth by Cynthia Moss of Amboseli Elephant Research). For forty-nine years, he wandered the plains and woodlands of the Amboseli ecosystem in East Africa. A gentle soul like most elephants, he was so relaxed that in 2007, he allowed me to come within a few feet of him to take his portrait.

Two years later, in October 2009, it was perhaps this level of trust that allowed poachers to get close enough to kill him and hack out the tusks from his face.

This book, Across The Ravaged Land, is the final book in the trilogy that I began in late 2000. Being something of a natural pessimist (always tempting to actually just say “realist”), I always felt that I was potentially making a final testament, an elegy, to the extraordinary natural world of East Africa, and the wild creatures that inhabited it. Back then, in my first book, On This Earth, I photographed what I saw as something of a paradise, an Eden. And it was, compared to what is happening today in 2013. But even thirteen years ago, my pessimistic mind did not conceive that things would turn this bad, this quickly.

As I write, there is a continent-wide apocalypse of all animal life now occurring across Africa. When you fly over such a vast continent with so much wilderness, it’s hard to imagine that there’s not enough room for both animal and man. But between an insatiable demand for animal parts and natural resources from other countries, and a sky-rocketing human population, the animals are being relentlessly squeezed out and hunted down. There is no park or reserve big enough for the animals to live out their lives safely.

The statistics are finally, belatedly, starting to become known, and they need repeating:

An estimated 30-35,000 elephants a year are currently being slaughtered across Africa. That’s 10 percent of the elephant population every year.

Fed by the massively increased demand from China and the Far East, ivory prices have soared from $200 a pound in 2004 to more than $2000 a pound in 2013. China’s population is 1.3 billion and counting, and with 80% of its fast-growing middle class keen to buy ivory in some form, its price will only keep spiraling upwards. (It barely merits stating the obvious: that ivory is never more beautiful than when thrusting magnificently out of the face of an elephant).

As for rhino horn, it’s now more expensive than gold in the Far East, as the last rhino are gunned down to provide phoney ‘medicine’ for men with failed libidos.

There are an estimated 20,000 lions left in Africa today, a 75 percent drop in only twenty years. Most of this decline is due to conflict with the fast growing human population. But increasingly, lions are killed for body parts like claws, bones and teeth, again for the Asian market, now that tigers are too hard to procure. It has become so bad that there are next to no lions left outside the parks and reserves.

Viewing the steep downward slope on the graphs, it means this: at the current rate of slaughter, there will be no elephants, no lions, no cheetahs left in the vast expanse of the African continent within fifteen years.

The only place you will be able to see them is in the sad, drab confines of zoos. Or in fenced areas that constitute barely more than a glorified zoo. Once again, man is on the path to systematically exterminating entire species of his fellow creatures in the natural world. Will humanity learn and change as a result? Based on history, the despairing answer is no.

It all sounds fairly bleak, and much of the future inevitably will be. But there is a “however...” There has to be a “however...”

But we have to be prepared and willing to engage in the most almighty fight for it....

In July 2010, I returned for the first time in two years to the Amboseli ecosystem, a two million-acre area bordering Kenya and Tanzania in the shadow of Mount Kilimanjaro. Over the previous six years, I had spent many months photographing the elephants that inhabit this region. As a result, I had been fortunate to come to know some of these amazing creatures intimately.

Whilst there in 2010, I learned about the killing the year before not only of Igor, but others as well, like Marianna, the matriarch purposefully leading her herd in the photograph below.

Two years later, in October 2009, it was perhaps this level of trust that allowed poachers to get close enough to kill him and hack out the tusks from his face.

This book, Across The Ravaged Land, is the final book in the trilogy that I began in late 2000. Being something of a natural pessimist (always tempting to actually just say “realist”), I always felt that I was potentially making a final testament, an elegy, to the extraordinary natural world of East Africa, and the wild creatures that inhabited it. Back then, in my first book, On This Earth, I photographed what I saw as something of a paradise, an Eden. And it was, compared to what is happening today in 2013. But even thirteen years ago, my pessimistic mind did not conceive that things would turn this bad, this quickly.

As I write, there is a continent-wide apocalypse of all animal life now occurring across Africa. When you fly over such a vast continent with so much wilderness, it’s hard to imagine that there’s not enough room for both animal and man. But between an insatiable demand for animal parts and natural resources from other countries, and a sky-rocketing human population, the animals are being relentlessly squeezed out and hunted down. There is no park or reserve big enough for the animals to live out their lives safely.

The statistics are finally, belatedly, starting to become known, and they need repeating:

An estimated 30-35,000 elephants a year are currently being slaughtered across Africa. That’s 10 percent of the elephant population every year.

Fed by the massively increased demand from China and the Far East, ivory prices have soared from $200 a pound in 2004 to more than $2000 a pound in 2013. China’s population is 1.3 billion and counting, and with 80% of its fast-growing middle class keen to buy ivory in some form, its price will only keep spiraling upwards. (It barely merits stating the obvious: that ivory is never more beautiful than when thrusting magnificently out of the face of an elephant).

As for rhino horn, it’s now more expensive than gold in the Far East, as the last rhino are gunned down to provide phoney ‘medicine’ for men with failed libidos.

There are an estimated 20,000 lions left in Africa today, a 75 percent drop in only twenty years. Most of this decline is due to conflict with the fast growing human population. But increasingly, lions are killed for body parts like claws, bones and teeth, again for the Asian market, now that tigers are too hard to procure. It has become so bad that there are next to no lions left outside the parks and reserves.

Viewing the steep downward slope on the graphs, it means this: at the current rate of slaughter, there will be no elephants, no lions, no cheetahs left in the vast expanse of the African continent within fifteen years.

The only place you will be able to see them is in the sad, drab confines of zoos. Or in fenced areas that constitute barely more than a glorified zoo. Once again, man is on the path to systematically exterminating entire species of his fellow creatures in the natural world. Will humanity learn and change as a result? Based on history, the despairing answer is no.

It all sounds fairly bleak, and much of the future inevitably will be. But there is a “however...” There has to be a “however...”

But we have to be prepared and willing to engage in the most almighty fight for it....

• • • • •

In July 2010, I returned for the first time in two years to the Amboseli ecosystem, a two million-acre area bordering Kenya and Tanzania in the shadow of Mount Kilimanjaro. Over the previous six years, I had spent many months photographing the elephants that inhabit this region. As a result, I had been fortunate to come to know some of these amazing creatures intimately.

Whilst there in 2010, I learned about the killing the year before not only of Igor, but others as well, like Marianna, the matriarch purposefully leading her herd in the photograph below.