The animals came first.

Not the photography, but the animals.

Or to elaborate, my love of animals came first. Photography was merely the best medium to convey my love of, and fascination with them.

I first visited East Africa in 1995 whilst directing “Earth Song”, a music video for Michael Jackson. I fell in love with the place and with the animals. That’s not very surprising - it has a similar effect on many people. But that experience shifted my focus in terms of what I wanted to say about the world. So I spent the next few years trying to find feature film projects that dealt in sophisticated ways with the subject matter of animals and the environment. But it was hard to find any story in which the money people were sufficiently interested.

Directing is a frustrating business. Vast precious tracts of your life, when, in theory, you are at your most creative and energetic, are consumed with projects that ultimately never see the light of day. You’re dependent on the money people to be able to create. And even if you’re fortunate enough to finally get that money, the compromises involved can take you a long way from your original vision. For so many in the film ‘industry’, you’re living for tomorrow, not in the present, unable to simply do what you are desperate to do: CREATE.

Photography, however, allows you to just go out and create how you want, what you want, when you want. You’re answerable to no-one. You’re in control of your creative life. Joy.

So at the end of 2000, I went back to East Africa, this time to photograph. The irony is that I had chosen a subject matter - animals - over which I had no control whatsoever.

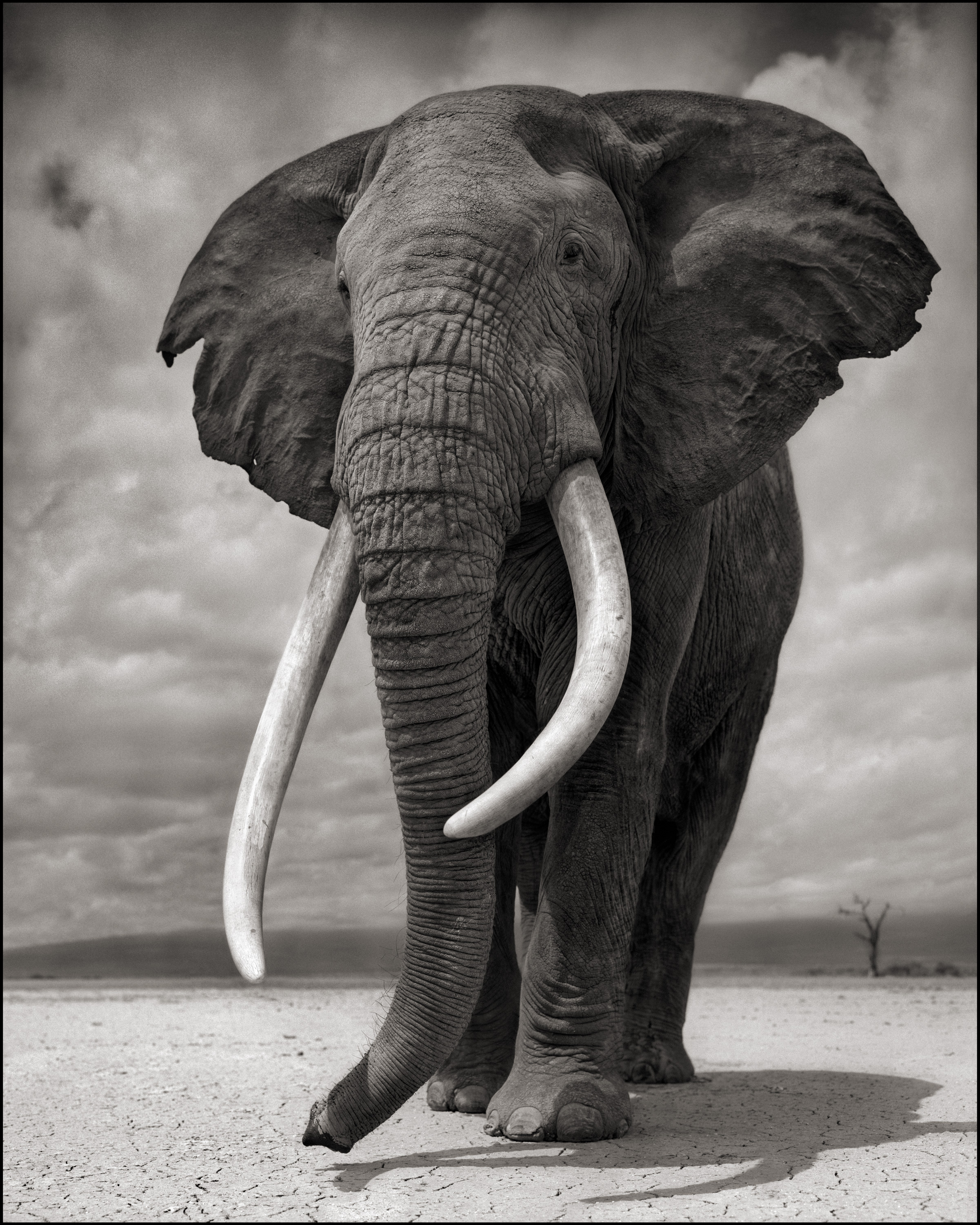

From the outset, I had a vision in mind: I wanted to create an elegy, a likely last testament to an extraordinary, beautiful natural world and its denizens that is rapidly disappearing before our eyes. I wanted to show these animals as individual spirits, sentient creatures equally as worthy of life as us.

I chose to photograph in black and white, because aside from the purely aesthetic (the compelling graphic nature of black and white imagery), it accentuates the impression of the images belonging to another much earlier time. As if these animals in the photographs are already long gone, already dead.

Photographing with film, as I have done throughout, also gives the images an air of timelessness that digital could not.

The camera of choice was, and has remained to this day, incredibly impractical for what I do: a medium format Pentax 67II with waist level viewfinder. Just 10 shots per roll, no zoom, no auto-focus, no auto metering, no motor drive, no image stabilizer lenses.

In fact I only use two fixed lenses, the 35mm equivalent of a standard 50mm and a 100mm, not out of necessity, but out of choice.

In other words, everything I do seems to be perversely, masochistically designed to increase my chances of messing up and losing the maximum number of shots in the process.

In 2011, the temptation to live an easier life - both practically and emotionally - finally seduced me. Frustrated by the number of shots I was losing shooting with film, I brought a Hasselblad 60 megapixel medium format digital camera to Africa with me. I took photos side by side with my film camera. The digital camera’s images were sharper. They had more detail in both the shadows and the highlights. The digital camera made photographing very, very easy.

And I hated it. For me, the images were too clinical, too sterile, too devoid of atmosphere. Just too....perfect. In fact, had I photographed using a digital camera from the beginning, I’m not sure that I would have liked a single photograph that I had ever taken.

So as long as there is film available to buy, and airport security people that can be gently persuaded to hand check the precious vulnerable exposed rolls, I will continue to photograph with film. And I’ll continue to lose endless shots along the way. So be it.

The first two books in the trilogy were entitled On This Earth and A Shadow Falls. The title of the final book, Across The Ravaged Land, completes the sentence and the trilogy:

On This Earth, A Shadow Falls Across The Ravaged Land.

I may have had a clear vision from the outset of how and what I wanted to photograph, but with the horrifying acceleration of destruction over the last few years, I could no longer photograph an idyllic view of what I saw. Thus the title of this book.

In the past few years, every time I photographed an elephant, I wondered if this would be the last time I would see him, and photograph him, alive. Sometimes it seemed like a miracle when one of my favorite elephants, like Craig, the beautiful giant-tusked male below, reappeared after months of no sightings.