This happened two days ago, near Amboseli Lake.

In the early evening light, a huge herd of elephants—some two hundred, more than I'd ever seen together—came shuffling softly toward me through the feathery grass. As they glided by me, heading in the direction of the setting sun, the sound—an incredibly gentle, soft shuffle that completely belied their four-ton weight—was almost as sublime, as magical, as the sight.

I tried to find a frame to capture the magnificent sight, but no angle—high or low or panoramic—came close to distilling the experience of these elephants. To try to capture with my camera the sheer beauty, poetry, and scale of the vision before me was, well, pointless.

So I just sat back, and let the long, gentle flow of elephants drift past me. A moment never to be photographed, but always remembered.

It’s happened before, of course.

There was the early morning in January, on the southern Serengeti plains. A dozen giraffes were running together, with that extraordinary slow-motion grace, across the green velvet carpet of new grass.

I drove alongside the galloping giraffes, which were backlit against the Gol Mountains beyond, for a couple of miles. Speeding along at thirty miles an hour, I photographed the giraffes' semisilhouetted figures, high on the sight and the speed. But later, when I looked at the developed photos, I saw that, amid the clutter of legs and necks, nothing of that wonderful grace in motion had been captured in a single still image.

And there was the morning one August, in the rolling hills of the Maasai Mara. By then, I'd seen a few wildebeest migrations on the flat plains of the Serengeti to the south, but nothing, nothing had prepared me for the vision I saw up here: a vast medieval army of tens upon tens of thousands of wildebeests, spreading across each and every hill and valley for as far as I could see.

I panned my camera across this epic sight, looking for something to meaningfully frame. It was utterly futile. I never even clicked the shutter.

Why begin this piece with my failure as a photographer? Because it's one way I can perhaps begin to describe the extraordinary subject matter here.

Of course, this book will hopefully bear witness to the fact that, upon occasion, I have actually managed to click the camera shutter. And there have been instances when something of the essence of that experience, at that moment in time, has permeated the final photo.

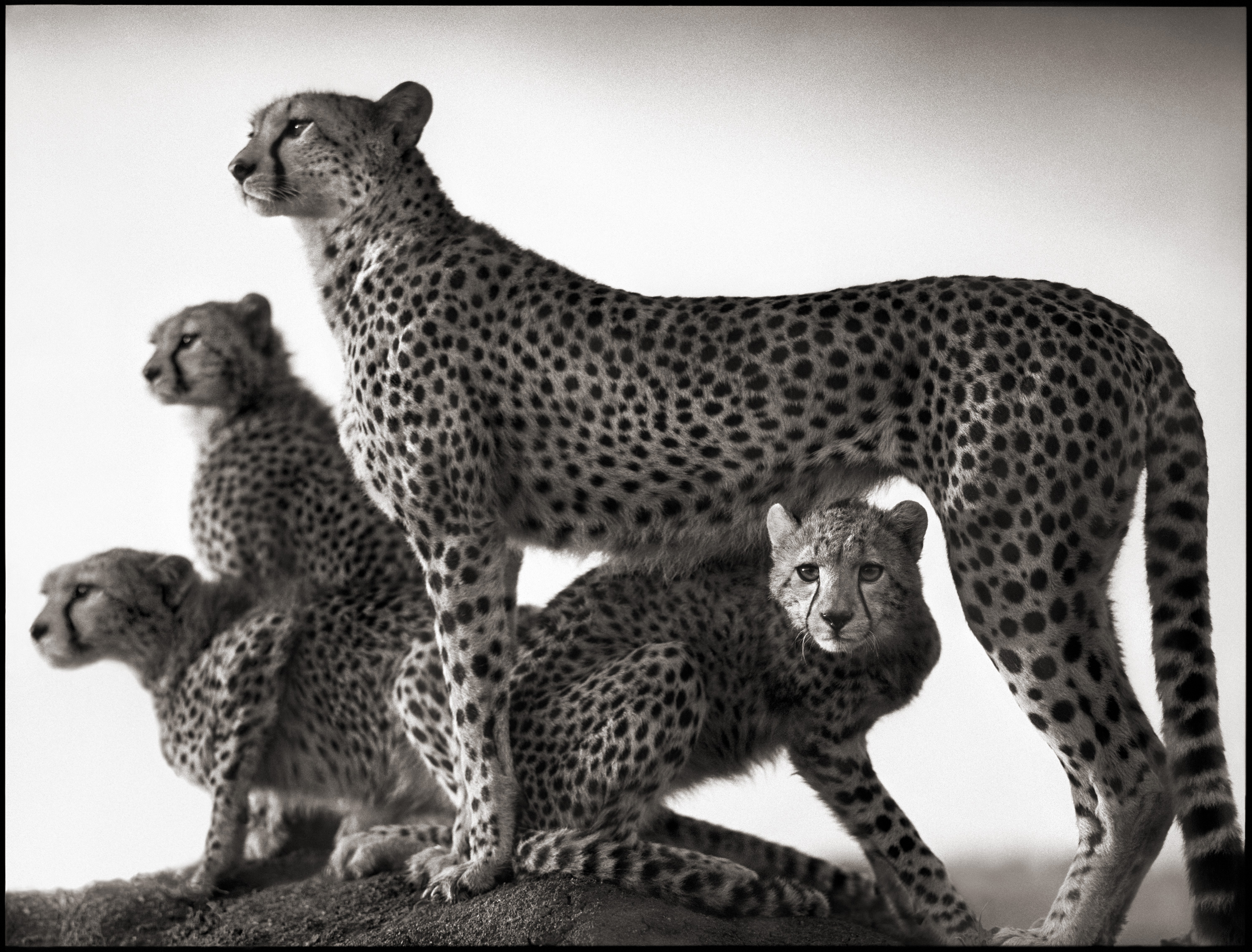

Perhaps some of the simplest, quietest captured moments, precisely because of their simplicity, have come closest to capturing the essence of being there, in that moment, with that particular creature. And many of these moments have been achieved by one not-so-simple thing: getting very, very close to the animals.

I don’t use telephoto lenses. With a telephoto lens, the photographer is generally framing the animal against earth or scrub that has little poetry or beauty, whereas I want to see as much of the sky and landscape as possible. I want to frame the animals within the context of their environment, their world.

I want to get a real sense of intimate connection with each of the animals—with that specific chimp, that particular lion or elephant in front of me. I believe that being that close to the animal makes a huge difference in the photographer’s ability to reveal its personality. You wouldn't take a portrait of a human being from a hundred feet away and expect to capture their soul; you'd move in close.

So I take my time and get as close as I can, inching my way forward little by little—either in car or on foot—often to within a few feet of the animals. And the more I feel like they’re presenting themselves, posing for their portrait, the more I seem to like the final result.

To me, every creature, human or nonhuman, has an equal right to live, and this feeling, this belief that every animal and I are equal, affects me every time I frame an animal in my camera.

With that in mind, I sometimes wonder what stops me from photographing the wild animals of North America, where I live; or from photographing my own dogs and cats; or from photographing farm animals, the most horrifyingly abused and maligned of all living creatures in the modern industrial world. Maybe one day I will photograph all these animals—those closer to home and less exotic, or the unseen billions of “raised-for-food” animals equally deserving of, but callously denied, a decent, humane life.

But for now, there in Africa, I find myself obsessively returning to those faces, those shapes, those landscapes, for there is something profoundly iconic, mythological even, about the animals of East and Southern Africa. There is also something deeply, emotionally stirring and affecting about the plains of Africa—those vast green rolling plains punctuated by graphically perfect acacia trees under the huge skies. It just gets you. Gets you in the heart, gets you in the gut.

At the end of the day, I’m not interested in creating work that is simply documentary or filled with action and drama, which has been the norm in the photography of animals in the wild. What I am interested in is showing the animals simply in the state of Being.

In the state of Being before they are no longer are, Before, in the wild at least, they cease to exist. This world is under terrible threat, all of it caused by us.

My images are my elegy to these beautiful creatures, to this gut-wrenchingly beautiful world that is steadily, tragically vanishing before our eyes.

And so it is that tomorrow morning I’ll head back out once again OK to find the elephants, on their daily trek to water, to see if this time...this time I can capture on film the splendor and soul of these creatures, and the place they live.

For while it’s still there, while the animals are still there, I’ll keep trying. How could I not?

© Nick Brandt

Near Amboseli, Kenya

May 25, 2004