The first time I saw Nick Brandt’s pictures, I felt emotionally involved. Gazing at some of the images, such as those of the cheetah standing in the fork of an acacia tree, the marabou storks roosting in the upper branches of a grove of trees, and the wildebeest crossing the Mara River, I found I was caught up in the experience of the photographer. It was as though I was sharing that moment when animals and landscape merged into one exquisite whole, the moment when the image was captured.

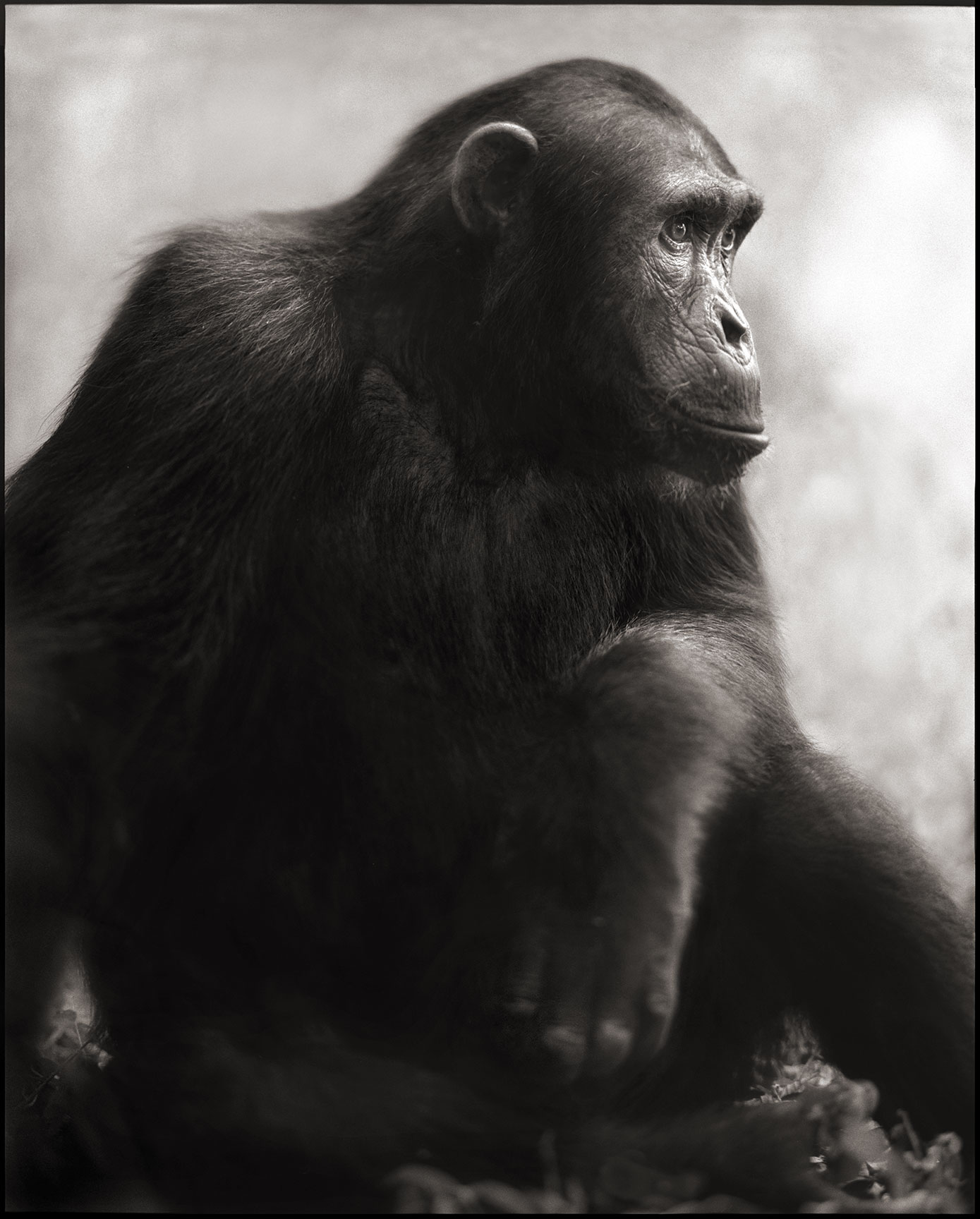

Nick has focused on photography of wildlife and the natural world of Africa as an art form. Many of his images have the magnificent compositions of classical landscape paintings: the image of hippos gathered near the banks of a river, for example, is reminiscent of a landscape by the nineteenth-century English painter John Constable. And many of his close-ups look as if the animal has agreed to pose for a studio portrait—especially the photographs of the chimpanzees and lions. Yet not only were these animals wild and free, but Nick did not even use a telephoto lens; instead, he relied on his patience and ability to quietly, unobtrusively capture each subject’s true image.

Nick has depicted the individuality of his animal subjects—it is almost impossible to look through this book without sensing the personalities of the beings he has photographed. I think I knew from the very beginning that the lives of individual animals mattered and had meaning in the great scheme of things. My forty-five years of learning about and learning from chimpanzees has only strengthened this conviction—as do Nick’s photographs. Look at the intelligence and self-awareness that gleams in the eyes of the chimpanzees. Sense the absolute self-confidence of the lions—especially the lioness in Ngoronogoro Crater, who gazes out over her hunting grounds, supremely aware of her own power.