THE HOUSE THAT BROKE IN HALF

SURVIVORS: THEIR PAST AND PRESENT

THE PEOPLE

April 30, 2019: Betty had a house in the morning. By sundown, it was gone, destroyed by a landslide.

That day, she had gone to work in La Paz with her daughter Abi, less than a year old at the time. Around noon, she saw all the missed calls on her cell phone. The rainfall was much heavier than anyone was accustomed to, but the disaster was made far worse because the homes had been constructed on a former landfill. Most of her neighbors had also lost their homes in the mud and rain.

Betty and her husband were forced to live in tents at a refugee camp. They had borrowed from the bank for the construction of that house, and she currently continues to pay the installments of that loan, a loan for a house that no longer exists.

The trauma persists, as she says that sometimes she unconsciously realizes that she is looking for cracks in the ground, and when the rain falls, she cannot help but feel fear.

Little by little, they built their house. Carmen worked as a bricklayer’s assistant with her husband, with whom she had two children. They were in the process of adding rooms for Carmen's brother. Carmen set up a neighborhood store, and felt complete.

Everything changed one Saturday in February 2011, the day of the mega-landslide in La Paz. Caused by prolonged heavy rains, it was the worst that anyone, up until that point, had seen.

In the adjoining neighborhood, some houses were already beginning to be evacuated. Carmen went there and began helping people rescue their belongings. But after a few hours, Carmen realized that the disaster was going to be worse than originally thought. She went back to her home, to discover that houses behind hers were already beginning to collapse.

Carmen was coming out of her house with rescued belongings when the windows and doors began to smash. Outside, she turned back to see the house literally break in half. One half began to move in the opposite direction to the other half.

Ten minutes later, the entire house collapsed. It was one of 400 homes destroyed that day.

But for Carmen, the tragedy did not end there. In the following years, after living in a refugee camp, her husband left her. Carmen tried to rebuild the home that she longed for so much. Recently, however, her eldest son committed suicide, due to problems related to his school performance.

And yet for the two weeks that Carmen was with us, even though she unsurprisingly says that she cannot hold back the tears at times, she was always a radiant, positive presence, helping production just because she wanted to make herself useful. She was such a strong woman, where most of us would have surely collapsed.

Carmen now has her own small grocery store in El Alto, La Paz.

Clementina, seventeen at the time of photographing, lives with her parents and brothers. Her father, Dionisio, is a farmer. He sees how dramatically the climate has changed for the worse.

Intense rains and out of season frosts, and hail have begun to develop in times that do not correspond to the planting calendar that he learned from his parents. Before, there were dates for the rains, and based on that they could organize themselves.

Dionisio sees how at the same time, the heat has also increased in the region, with a decrease in water for irrigation. Before, there was enough water for everyone in the community, but now they have to take turns managing water, which puts their harvests more at risk. New pests have also appeared in recent years, which are difficult to combat and that more than once have ended up ruining entire crops, with the inevitable economic repercussions.

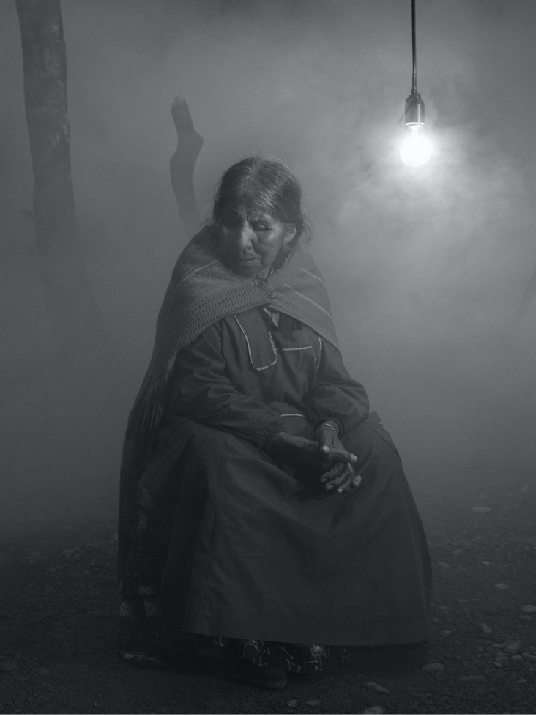

Eustaquia lost her home in the 2011 mega-landslide in La Paz. Caused by days of heavy rains, it was the worst that anyone, up until that point, had seen.

Eustaquia worked as a maid. After some years, she had managed to buy a small house in a hillside area of the city. Years later, she sold it to buy a piece of land closer to the city. It took a year and a half to build her new house. But she would only have it for three years.

Separated, she raised her only child alone. She lived in the house with her son and her daughter-in-law who had just had a baby. But the baby would only sleep one night in that house.

One fateful Saturday, as other neighbors’ homes began to collapse, they barely managed to get out with a few belongings. Then the floor of the patio split, and little by little the whole house was swallowed, sinking into a giant crack. Eustaquia sat in the rain until dawn in front of what was left of her house. They had lost everything.

They spent several years living in the tents of the refugee camp. Years later, her son tried to start a new life in another city. Before starting the new job, however, he was diagnosed with advanced tuberculosis. Weeks later, he died. Of course, Eustaquia still mourns the death of her only son, but finds comfort in her two grandchildren.

Florentino and his wife Ilaria are farmers. In December 2021, their land was destroyed by a flood, and on that day they lost all of their crops, as well as pumps and pipes that Florentino had installed for irrigation. There had been a few other floods in the past, but nothing like this one.

Florentino believes that it will take about ten years to earn the necessary money to get the land back to a place where it can be planted again. (The money that the family made for being part of this photo shoot helped toward this.) Meanwhile, he and his wife Ilaria work for other landowners to try to raise the money to repair their land.

They also have six children, including Marisol and Christiano, featured in these photographs.

Ilaria is the wife of Florentino. Their story is told above under Florentino’s photo.

Marisol, eleven years old when photographed, is the daughter of Florentino and Ilaria Godoy, whose history is told above. By coincidence, Lucio Vela, also prominently featured in this series, is Marisol’s godfather. He set aside some of the money he earned on this shoot to help pay for Marisol’s education. This was so good of him, especially because we all think that Marisol is exceptionally smart and engaged.

Jaime is a farmer, living with his wife and two children. Two years ago, a frost wiped out almost the entire crop in some of his fields. Last year, a large hailstorm did the same. Jaime says that such events did not happen so frequently in the past.

One of the most terrifying problems in the near future will be a dramatic drop in water supply, as the glaciers on Cerro Illimani, Bolivia’s second highest mountain, rapidly melt and shrink. The glacier acts as a natural reservoir, providing the only source of water during the dry season to Indigenous communities that use this water to irrigate their crops. Indeed, throughout the Andes, glaciers are melting at an alarming rate as temperatures have been rising faster at higher altitudes. The glaciers are expected to disappear over the next twenty to forty years, which will be a calamity since they provide the main source of water across most of South America.

As Jaime says, “In another twenty years, there will be no ice, and then what will happen to all the agriculture here? It will be our end.” He expects that this would not only force many in the community to become climate refugees and move elsewhere, but it would also leave La Paz with a much-diminished food supply.

"The earth is already tired,” Jaime says. He hopes that his children will not follow the path of farming, which he believes now has little future for him.

Juana grows peanuts and beans on about two acres. But the increased incidence of both droughts and floods, extreme heat and then cold, and winds, has dramatically impacted production. Lost harvests, once upon a time extremely rare, have become common for all of the farmers around her.

The river by her has also become so contaminated due to mining, that now not even the fish can be eaten safely. That contamination, and the sheer amount of plastic pollution, has resulted in much reduced fish populations.

Juana is also a naturopath, using plants from the nearby forest, which is a knowledge passed down through generations. Seventy-seven years old at the time of photographing, she had an energy and radiance of someone much younger, and like all the people in these photographs, was unfailingly gracious and patient.

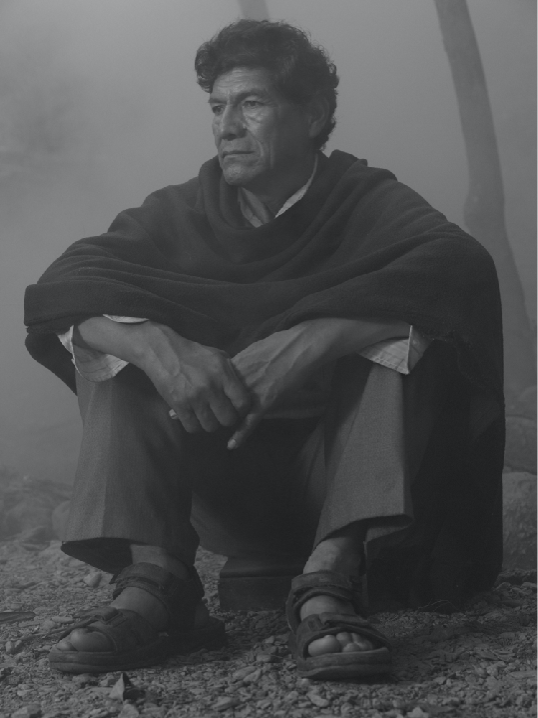

Lucio, a farmer, lives with his wife and daughter. In 2021, floods on a scale never before seen in the area, swept away everything in their path. Lucio lost all of his crops, and in its current state, more than half his land is now useless for planting as it is covered with stones, sand, and mud.

He, like many in the community, is in a precarious economic situation, since he had everything invested in his crops. Lucio is trying to persuade the local authorities that a retaining wall be built on the river, but if this doesn’t happen, he is pessimistic that the community can recover. And given the increasing regularity of climate change-induced events, he thinks that it is only a matter of time before this happens again.

Lucio sees a huge change from when he was a child. People are beginning to abandon their farms and taking safer jobs like construction work.

A strong, proud man, he was on the shoot for quite some weeks, and would often help the crew with their work, although he did not need to. The money he earned on the shoot helped pay off the debts from the loss of his land.

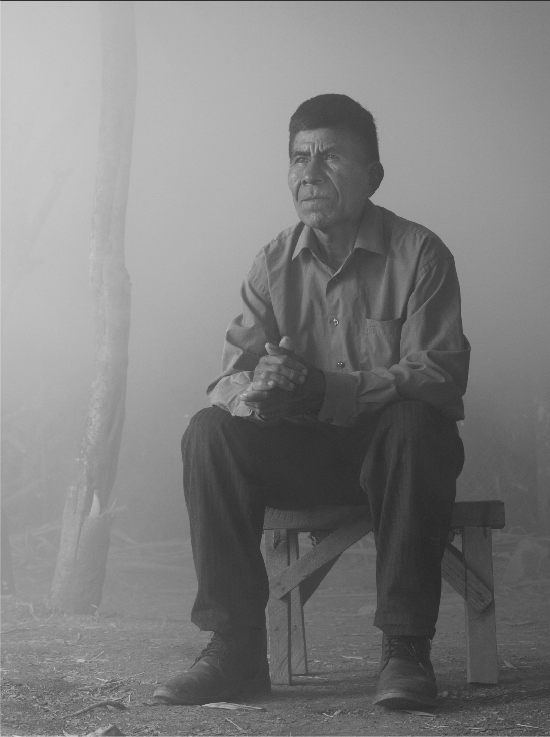

Luis is a teacher at the community school, and also a farmer. In 2021, he lost practically all of his crops due to flooding from overflowing rivers. He remembers that events of this type never used to happen in the community, and that weather events have changed enormously.

He is aware that these changes and natural disasters are the result of global warming, so he tries to teach this to the children of the community, hoping that it will generate a change in attitude toward these problems.

2014. The heavy rains came and did not stop for several weeks. The river close to Ruth’s house burst its banks and rose to such a degree that it reached the roof of Ruth’s house. Ruth was only able to save a few things.

Water and mudslides destroyed and damaged more than 60,000 homes. Many lives were lost, and many lost their livelihoods. About 150,000 cattle also died, as well as countless wild animals.

Ruth, pregnant at the time, moved to tents donated by the municipality. Now a single mother, she works to support her children.

The worst flood in sixty years, the level of destruction was felt to be caused not just by climate change, but also by deforestation on hillsides, increasing runoff into the already swollen rivers

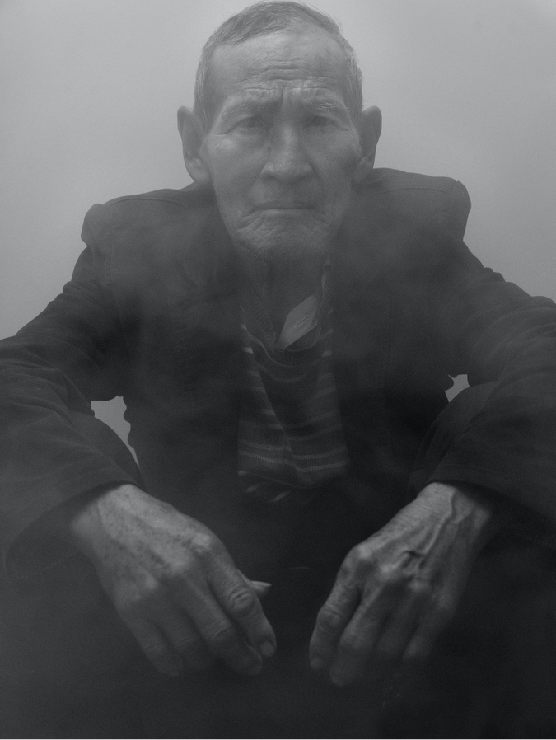

For many years, Samuel and his brother Adolfo worked in the refuge on the Chacaltaya Glacier, the location of Bolivia’s only ski resort, and the world’s highest. It was a very popular skiing destination for people from around the world.

But in the 1980s the amount of snow began to decrease. The glacier diminished by more than 90 percent by the late 1990s, and disappeared completely in 2009, even faster than expected.

Tourists no longer came. The resort shut down and is now a ghost town. Samuel and his brother Adolfo were left without a job, and his family could only support themselves because of the artisanal work of his wife Martha. Samuel goes up to the shelter from time to time, remembering the glorious past of the mountains that will never be the same again.

Temperature increases of as little as 0.1°C per decade can cause glaciers to shrink dramatically. Unsurprisingly, with climate breakdown, glaciers across South America have retreated, shrunk, and vanished altogether with ever greater speed.

In 2014, intense extended rains caused a river to burst its banks near the Rocobado family’s house. The water swept away their animals and chickens. As the house began to flood, Calixto and his family tried to save what they could, but their efforts were in vain. His eldest son fell into the river, but fortunately neighbors and relatives helped Calixto rescue him.

After two years of struggle, living in fear that it would happen again, Calixto moved his family to another region, where he now harvests rice, corn, and yucca to support his family. Sure enough, there have been more severe floods back in the region where he grew up, again more severe than what he saw growing up.

The 2014 heavy rains and ensuing floods affected a large area of Bolivia, flooding more than 100,000 acres of land, submerging villages, killing at least forty people and an estimated 150,000 cattle, and threatening hundreds of thousands more people with starvation.

Valeriano and his wife Susanna were among those. The rains, never as heavy as that in Valeriano’s lifetime, destroyed all his crops and the floods swept away his animals.

However, it’s not just climate change intensifying the floods. It is also deforestation, in this case at the headwaters of the Amazon basin. As a result of so much cleared ground, there is far more erosion and attendant lack of absorption of rainfall.

After 2014, Valeriano and Susanna moved their crops to different, less vulnerable land, when, sure enough, the floods came again in 2018.

Vicente lives in the cold highlands of the Oruro region. He farms vegetables and raises llamas.

The area is semi-arid, so with climate change the hardships for the local people have only become greater in recent times.

For Vicente, a lethal combination of drought on the one hand, and unnaturally intense hailstorms on the other, have wiped out his crops. His livestock have been weakened and sickened, and the calves die from the excessive cold. And then, to cap it off, in the months before the shoot, floods ruined his seeding crops and caused abortions in his animals.

THE ANIMALS

For Ajayu, I want to use the words of Marcelo Levy, founder of Senda Verde with his wife Vicky Ossio:

“The animals are the heart of Senda Verde. It’s because of them, of course, that the sanctuary exists.

It’s because animals are extracted from their natural habitats, from their families, their mothers needlessly killed. They are transported to cities where they are kept in unthinkable conditions, to be sold as pets, restrained with chains or ropes, starving and thirsty. Deprived of their basic freedom. They undergo extreme suffering, illness, and physical and emotional traumas, so extreme that perhaps only one of out of ten survives.

The animals that arrive at Senda Verde bear huge psychological scars. They are nursed back to health and become part of the Senda Verde family.

Ajayu’s story is one of the saddest of the animals living in Senda Verde. But it is also the story of many of the animals. His case created a lot of awareness regarding wild animals in Bolivia.

In 2016, when he was four years old, he was brutally wounded by people in a rural community, who threw rocks at his face and hit him repeatedly with sticks. His head, nose, and jaw were severely fractured. Both eyes were injured, which has left him blind, and with his sense of smell almost gone.

No one is certain, but we think the likelihood is that his mother had been killed when he was a cub, and that he was being kept in captivity in a cage, as he had the teeth of an old bear, due to likely giving him fermented corn. We think that one day he managed to escape, and that he was chased to push him back into his cage, which injured him badly in the process.

When Senda Verde received Ajayu, he was obviously traumatized, blinded, having experienced shocking physical trauma.

After some scans and surgeries, for twenty-four days, he did not eat and barely drank. He did not want to live. Vicki and I took care of him 24/7. At many points during those ensuing dark weeks, he seemed to be saying goodbye, let me rest.

We lost hope, but before finally giving up, I did one last thing. I prepared a special protein shake and forced him to drink it. Amazingly, he accepted it. And for us, that was the sign. He wanted a second chance. From that day on, he started to recover. He had a whole team of multi-country specialists all trying to help him.

After sixteen months of convalescence and demanding rehabilitation, of compassionate commitment and careful monitoring, Ajayu regained confidence, trust, and hope. Today, despite his blindness, he is a very affectionate, strong, and magnificent bear.

What they did to Ajayu is a crime. For us, it is one of the most, if not the most horrendous experiences we have had. But because of him and so many innocent victims of cruelty and suffering, we at Senda Verde are never going to give up protecting and restoring this magnificent planet.”

Apthapi is a lowland tapir, around eight years old when photographed. He was rescued when just five to six months old by the police from a hotel where they kept animals for entertainment. The animals were taken to La Paz zoo, which in turn sent Apthapi to Senda Verde, as it was too cold in La Paz.

Apthapi’s mother was probably killed when Apthapi was very young, so he was malnourished, which is why he is smaller than average tapirs (tapirs are the largest mammal in South America and can weigh up to 300 kilograms.)

Tapirs are officially vulnerable with populations declining (what animal population isn’t?). They are very exposed to local extinction due their slow reproduction and, as usual, hunting—for their meat and hides.

Habitat loss is also a major factor. In 2019, nearly fifteen million acres of land were burned in wildfires across Bolivia. This was mainly as a result of corporations’ desire to use the land to produce soy and coca leaves, and for cattle farming, and also of course, partly as a result of climate change and the accompanying droughts. In 2020, another ten million acres burned. Like all animals, as the fires hit their homes, they are forced into areas where they are even more vulnerable to being hunted and killed.

Arco Iris, a scarlet macaw, is perhaps fifteen years old. He was confiscated in a group of animals being sold in a market in one of Bolivia’s cities.

Due to habitat destruction and trafficking, the scarlet macaw population is declining and vulnerable.

Capy, a capybara, was brought to Senda Verde when she was four to five months old. Her family had been killed when she was a baby. Initially rescued by some volunteers, she was kept in an office on the fifth floor. When she arrived at Senda Verde, she didn’t know what soil was, and was afraid of the water (capybaras spend 65 percent of their life in the water).

Capybaras are the largest rodents on the planet. For the pet trade, they have to kill the mother because they will never let their babies go. But once capybaras grow larger, they are usually abandoned by the pet owners.

Capybaras are hunted for their meat and hide, and even for grease to be used in pharmaceuticals. In Bolivia, some are also hunted for use as bait.

CHASCAS

Chascas, a spider monkey, is about three years old. Senda Verde received a call about Chascas after her mother was killed in order to get the babies. This was a rare case where the mother had twins. Both siblings were kept by a family, but the male died when both fell from the roof while playing.

Once she arrived at Senda Verde, around five months old, Chascas would have nightmare flashbacks, screaming, panicking, every night for a couple of years. Now, however, Chascas is a very happy, free-roaming monkey, part of the gang, and loves new baby arrivals.

The black-faced spider monkey is listed as endangered, with an estimated 50 percent population decline over the past fifty years. Habitat loss from deforestation—for cattle farming, agriculture, mining, and of course logging—is one of the major reasons. But also, as usual, they are hunted illegally for food, and babies are captured for the illegal pet trade.

ECHO

Echo, an owl monkey, was about four months old when he was rescued from a market where he was being sold illegally. Owl monkeys live in troops of three to five individuals, usually father, mother, and offspring. In captivity, they will not accept a member that is not blood-related to them, and because of this it’s difficult to care for them.

The reasons for the declining owl monkey population are the same as so many of these animals: deforestation for timber, agriculture, cattle ranching, mining, and illegal coca leaves; and of course, the illegal wildlife trade. Owl monkeys are also sent to the United States for biomedical and ophthalmological research (many owl monkeys in captivity in the US are missing one eye as it was removed for research).

Hernak, photographed when he was aged seven, was being sold on Facebook (sigh), when he was a just a baby, after the mother was killed. He was sent to the city of Santa Cruz, where he was kept in a temporary animal shelter. While there, he had surgery for a fecal impaction, and during recovery Hernak opened the stitches. He was found in the morning with his intestines exposed and was rushed to the hospital. Somehow, he survived this.

Hernak now lives in a large enclosure on a forested hillside at Senda Verde. Like Tarkus the bear, he seems endlessly curious and energetic.

As always, the reasons for the decline in jaguars is multifaceted: habitat destruction from deforestation to an increasing number of wildfires; killing by livestock owners who pay their employees extra to shoot them, to feed an increased demand from China for the fangs of the jaguars. The supposed good luck, fortune, protection, and vitality offered by jaguar teeth—merely an extension of the Chinese belief that Asian tiger parts offer the same benefits—is at the heart of the demand. Offering $100 to $400 per tooth for jaguar fangs, the money to be made is too hard for many to resist.

In addition to the skins and skulls, even the testicles are prized in China—as an aphrodisiac. (This is as insane as believing the same about rhino horn.) Chinese companies are going into partnership with the Bolivian government, stripping National Parks of resources, which makes matters worse.

With the cooperation of the local prison system, Chinese nationals have created a thriving industry in which inmates are forced to create products such as purses and bags from threatened wild animals.

Even though it is illegal in Bolivia to kill, consume, or traffic wild animals, the level of enforcement is frustratingly minimal, especially in national parks, where many of the nation’s wild and threatened animals live, and where poachers operate freely.

Hisca is a four-to-five-year-old spider monkey. She was held as a pet after being sold in a market. The “owners” did not know how to manage her, and she was brought to Senda Verde.

One big problem of wild animals that become pets is the poor diet they receive for long periods of time, which will eventually manifest in serious health problems. Another problem is that they are humanized to an extent that means they will never be accepted among groups of their own species, due to behavioral issues.

Hob was one of seven capuchin monkeys confiscated by the police from a market selling pet baby monkeys. Jame, the baby howler monkey also seen in this series, was clinging to him. This was a few weeks before he was photographed.

The crazy thing about trying to sell baby monkeys as pets is that most of them will die within a few days of being separated from their mothers. At Senda Verde, every single baby monkey that comes in has to have a human surrogate mother assigned to them. These ‘mothers’ are patient loving interns and volunteers who nurse the monkeys around the clock for many weeks. Meanwhile, the price of monkeys in these markets continues to go up and up, inevitably encouraging poachers to engage in this ever more profitable business.

There are a number of species of capuchin monkey in South America, of which several are critically endangered for the usual reasons of the illegal pet trade and habitat loss.

Jame, a howler monkey, was confiscated by the police from a market selling pet baby monkeys. This was only a few weeks before he was photographed. He arrived clinging to Hob, the baby capuchin monkey seen elsewhere in the series.

The mother would have been killed because they never give up their babies. But after that, most of the baby monkeys will die within a few days of being separated from their mothers.

At Senda Verde, every baby monkey that comes in has to have a human surrogate mother assigned to it as they cannot survive without one. These surrogate mothers are patient loving interns and volunteers who nurse the monkeys around the clock for many weeks.

It’s no surprise then, that howler monkeys have the highest mortality rate in captivity among all primates in the world. Only a few animal refuges in Bolivia know how to care for them. Senda Verde has more than any other.

Meanwhile, the price of monkeys in these markets continues to increase, inevitably encouraging poachers to engage in this ever more profitable business. Like so many monkeys in Bolivia and South America, howler monkeys are not just in decline because of illegal wildlife trafficking, but also because of habitat destruction.

Kaa, a boa constrictor, was twenty-two years old at the time of photographing him. The mother was taken out of the forest while she was pregnant, and she gave birth to thirty-five baby snakes. Most of them were sold as pets, and the rest released back to the wild. Kaa arrived at Senda Verde, brought by her “owner” in 2006 when she was six years old.

Snakes are considered bad luck in Bolivia and so are regarded as a creature to be killed. They are also killed for superstitious local medicine. And their population is also impacted by the exotic pet and snakeskin trades.

Kini, a female howler monkey, was eight when she was photographed. She was brought to Senda Verde from a neighboring town, burned down one side of her body. The burns were possibly the result of hunters setting fire to the forest to force monkeys down out of the trees. The mothers are killed, and the babies then sold as pets in markets.

It took Kini a long time to recover emotionally, staying in the house of the founders, Vicki and Marcelo. Once recovered, Kini always cared for the new baby monkeys that arrived.

Raising howler monkeys in captivity is extremely hard, and without close constant attention, orphaned babies will usually only survive a few days. However, Senda Verde never turns away an animal, even though every adopted monkey is a huge commitment, needing a human surrogate mother to take care of them.

Like so many monkeys in Bolivia and South America, howler monkeys are in decline from habitat destruction and illegal wildlife trafficking for the pet trade.

Lari, perhaps more than thirty years old, is an Amazonas farinosa, a southern mealy Amazon parrot, one of the largest in South America. He was confiscated by the police, who had found him as an illegal pet. Someone had removed a key feather to prevent him from flying.

There has been much trafficking of these species because as pets they are quiet and learn to talk easily. Because of this, their population is declining.

Luca, just a few months old in this photo, was confiscated from a market in Cochabamba, only a few weeks before this photograph.

Locally known as lucachi, and as titis, there are many species of lucachis in Bolivia. Like other species of monkeys, the mother is killed and the babies taken out of the wild to be commercially sold as pets. And like all the other South American primates, deforestation and loss of habitat are profound threats to the survival of the titi monkey. As everything from illegal coca farms to coffee plantations replace forests, it’s not just a one-time destruction, but the increasing human population’s need for further wood for building and fuel. Hunting is also a threat to titis, mostly for subsistence, to the degree that some populations have become extinct.

Nayra was two years old when photographed.

Senda Verde received an anonymous call from a high mountain part of the country. People there were going to hunt down and kill a puma that had been killing chickens. Apparently, while they were out hunting for the mother, three baby pumas were found. The thought was that the mother had probably already been killed.

Senda Verde managed to rescue two of the three cubs, probably no more than two months old. But when they were five months old, Nayra’s sister suddenly died from intestinal issues. However, today Nayra has grown into an active, engaged and healthy adult puma.

As humans spread further and further into wild habitat, it’s only a matter of time before the puma, also known as the Andean mountain lion, is listed as endangered. This is not just due to habitat destruction, but also to poisoning, as farmers try to protect their livestock

Pimienta came to Senda Verde during a year with an especially high rate of wildlife trafficking. She was three to four months old. She arrived with a lollipop in her hand. The young woman that brought her to Senda Verde said that her boyfriend sent her a package by bus as a gift, and inside the box was this baby spider monkey.

Silala, a spider monkey, was five years old at the time of these photographs. She was being sold in a town and was confiscated by local authorities who sent her to Senda Verde. Again, families are killed to get the babies.

Although Silala is very territorial, she adopted a baby that arrived recently, another victim from trafficking, and has proven to be an excellent mother to her adopted child.

The black-faced spider monkey is listed as endangered, with an estimated 50 percent population decline over the past fifty years. Habitat loss from deforestation—for cattle farming, agriculture, mining, and of course logging—is one of the major reasons. But, as always, they are also hunted illegally for food, and babies are captured for the illegal pet trade.

Taika, a yellow-footed tortoise, is sixty to seventy years old. Taika lived as a pet for fifty years in the city of La Paz, with an eighty-five-year old women that called Senda Verde, worried that something could happen to her due to her old age, and also because her son did not like Taika.

The species is currently endangered, not just because of habitat loss, but also because they are so easy to catch and so heavily trafficked, in this case for their meat and for the pet trade.

Tarkus was rescued as a three-month-old baby by the side of the road. His mother had been killed.

Tarkus, three years old when he was photographed, now lives in a large hilly and forested enclosure at Senda Verde. Always curious and engaged, it seems safe to say that he is happy. A single electrified wire fence kept him safely separated from humans during the shoot.

The only surviving species of bear in South America, there is only an estimated 2,000 to 2,500 left on the entire continent. The reasons are multifaceted: deforestation for timber and illicit crops such as coca (I saw large areas of “protected” national park in Bolivia deforested in this way); grazing areas for cattle farming; road construction; and mining. Complicating matters, protected areas, and some of the bear populations, are not large enough for the species’ survival throughout its range. Estimates put bear habitat loss at up to 4 percent a year.

Although protected by international trade laws, Andean bears are still illegally hunted for their meat and body parts. The gall bladders, much sought after in China, are used for various ailments without any scientific basis, and fetch high prices, as do the bears’ paws.

Tricia, a spider monkey, arrived about five years ago as an orphan baby, only a few days after her mother was killed. She was very shy, frightened, and skinny. It took the Senda Verde team a long time to build trust with her, but now, here she very much is.

The black-faced spider monkey is listed as endangered, with an estimated 50 percent population decline over the past fifty years. Habitat loss from deforestation—for cattle farming, agriculture, mining, and of course logging—is one of the major reasons. But, as always, they are also hunted illegally for food, and babies are captured for the illegal pet trade.

Zosa, a three-toed sloth, was perhaps eight months old when she was photographed here. She was confiscated by the police from a restaurant in December 2021. Along with many other animals, she was kept there to attract customers, after being bought as a baby in a nearby market town. Like so many other animals, her mother was killed.

Zosa now lives up in trees in the forest at Senda Verde.

Because sloths are the slowest-moving mammal in the world, these astonishing, sweet creatures increasingly meet terrible deaths. As more and more of the Amazon is destroyed by fires started by man, the sloths are too slow to be able to escape. And when the trees they inhabit in the forest are chopped down, the sloths come crashing down with the trees. Countless others are run over.